I’ve learned a ton during the past decade, thanks to reading, interviewing, and massive trial-and-error. I’ve distilled many of these lessons into today’s blog post.

Here are 17 lessons that can improve your money and life.

#1: Money Can’t Make You Happy, But Lack of Money Can Make You Unhappy

They say, “money can’t make you happy.” But that’s false.

Researchers have examined the link between money and happiness — and guess what? Money can make you happy, to an extent. Multiple studies found a significant correlation between money and happiness among people in low-to-middle income brackets.

More money = more happiness, up to a certain level. That’s not surprising. If you used to earn $30,000 per year, and now you earn $50,000 per year, this additional money makes a huge impact. You’re not as stressed.

The wealthier a household becomes, the more this effect diminishes. Each additional dollar in household income produces a smaller incremental boost in happiness.

What’s the tipping point? That’s up for debate. One famous study says there’s a huge correlation between money and happiness up to the first $75,000 in household income, after which it plateaus. Other studies claim that marginal gains start dropping off between $80,000 and $100,000, while yet other studies put the number closer to $160,000.

Of course, “enough” depends your family size and location. Earning $100,000 as a single person in Des Moines is different than $100,000 for a family of six in San Francisco. It’s oversimplified to discuss dollars in a vacuum.

But the takeaway is that while money can’t make you happy, lack of money can make you unhappy.

P.S. — You know that cliche, “I’d rather be happy than rich?” That’s B.S. The effect is either positive or neutral. There’s zero research that shows an inverse correlation.

#2: Experiences Make Us Happier Than Things

About a decade ago, University of Colorado psychology and neuroscience professor Dr. Leaf van Boven decided to unlock the key to happiness.

He surveyed hundreds of people about recent purchases they’d made, classifying these as either “experiential” or “material.” Then he asked about their self-reported happiness levels.

Can you guess the results?

If you want to be happy, spend money on experiences, not things.

Here’s a run-on sentence from Dr. van Boven’s report:

“Preliminary research suggests three reasons why experiential purchases make people happier than material purchases: (a) experiences are more open to positive reinterpretation, (b) experiences are less prone to disadvantageous comparisons, and (c) experiences are more likely to foster successful social relationships.”

Huh? Here’s what he’s saying:

First, experiences are subject to nostalgia bias. Memories get rosier over time. When we look back on that trip to Disney World, we don’t remember the long lines, fussy kids, or the dropped ice cream. We remember the highlights, like the smiles on our kids’ faces when they met their favorite characters.

Objects, on the other hand, depreciate over time. They wear out, break down, and the happiness we feel from them fades. We get more joy from looking forward to a purchase (anticipation) than we do from owning it (hedonic adaptation). Once we have an item, it’s easy to take it for granted.

Second, experiences have less of a “keeping up with the Joneses’” effect. Your neighbor’s amazing vacation in Costa Rica didn’t make your epic trip across Argentina less memorable. (Although these days, the Instagram effect might be muddling the line.)

Third, experiences help people bond with friends and family. And the happiness effect from those relationships is straightforward.

#3: Never Delay Gratification

I know, I know. This sounds counterintuitive.

Isn’t money management supposed to be the practice of delaying gratification? Aren’t we supposed to have a sucky “right now” for the sake of an awesome future?

Nope.

Here’s a framework shift: Don’t delay gratification; reframe gratification. Find gratification in index fund investing, buying rental properties, and watching your net worth grow.

Find gratification in home-cooked meals, driving a reliable used car, and not getting brainwashed by fancy labels. Find gratification in the fact that you can spend your Tuesday taking a random hike on a whim, because you’ve designed your life accordingly.

Delay gratification? Are you kidding me? Pffffft. I’m not delaying jack. When I build a pile of cash for the down payment on my next rental property, I feel effing awesome.

When I check my net worth and see the results of what I’ve built, I’m deeply gratified — much more so than I would feel if I bought a few extra pieces of plastic junk.

#4: Know Your “Millionaire Next Door” Number

Do you pass the Millionaire Next Door test?

The book The Millionaire Next Door explains how to calculate whether you’re a prodigious accumulator of wealth (PAW) or an under accumulator of wealth (UAW). The formula is:

Your age x your annual pre-tax income ÷ 10 = your target net worth

Let’s say you’re 35 years old and make $70,000 a year. You’d multiply 35 times $70,000 and divide that number by 10, for a target net worth of $245,000. If your net worth is higher than that, you’re a prodigious accumulator of wealth. If it’s lower, you’re an under accumulator.

If you’re a couple with commingled finances, take your average age and multiply it by your combined annual pretax income.

If you’re in your 30’s or older, crunch this number once a year.

Here’s the catch: If you’re in your 20’s, this formula won’t apply to you yet.

If you’re 25 and you make $70,000 a year, for instance, this formula would claim that your net worth should be $175,000. Buuttttt …. That doesn’t make sense. If you’re 25, this might only be your first or second year of salaried full-time work.

Ignore this formula until you’ve hit your 30’s. Once you’ve been in the workforce for a decade, then start crunching your TMND number.

#5: The Less You Try, the Better

In most professions, trying harder = getting better results. But when it comes to investing, the less you try, the better.

We see this in index fund investing. Frequent trading and micromanagement often produces worse results than a set-it-and-forget-it, buy-and-hold approach.

We also see this in real estate. Flipping houses is a ton of work and carries an added risk premium; a buy-and-hold strategy requires that you frontload the workload and then enjoy the results for decades to come. The passive approach creates a long-term recurring income stream. Double win.

The lazy, simple, couch potato portfolio might be your BFF.

#6: Simplify Everything

Find the simplest way to do whatever you’re doing. For example:

Index Investing:

You could spend hours and hours making micro-tweaks to your asset allocation, but why bother? Pick an allocation you’re happy with and move on.

Real Estate Investing:

You could fall down the rabbit hole of every available possibility: rentals, flipping, wholesaling, tax liens, residential, commercial, offices, warehouses, mobile home parks …

Nah.

Don’t attempt everything. Pick one niche and one strategy. Focus there. Let the rest go.

My niche is residential properties, and my strategy is buy-and-hold. That’s not because I believe it’s “better;” it’s because I’m simplifying. I’m choosing one investing style, deep-diving in an effort to create mastery, and staying focused.

Cash flow:

Don’t bother creating a detailed, line-item spreadsheet with a dozen-plus categories that micromanage your budget in excruciating detail. That’s unnecessarily complicated. Besides, how long are you really going to stick with it? Do you think that in five months, you’ll stay motivated enough to tally every item from the grocery store?

Stick to the anti-budget: yank your savings off the top, then chill out about the rest. Pick whatever savings rate you want — 10 percent, 30 percent, 50 percent, it’s your call. Transfer this into savings each month. Live on the rest.

You don’t need to create a hyper-detailed budget. These budgets introduce complexity into the system, and the more complex a system, the more likely that system is to fail.

Work life:

Find the 80/20 solution to every project. What activities give you the biggest return on your time, energy and attention?

Ask yourself, “what’s the ONE thing I can do [for my health, money, relationships, etc.] such that by doing it, everything else becomes easier or unnecessary?”

Workouts:

I don’t need to learn 40 different types of exercises. I need to know how to perform bench presses, deadlifts, squats, rowing, some cardio, and some stretching. My workouts don’t need to be more complicated than that. Find a routine that works for you and ignore the urge for shiny-object-syndrome when it comes to the latest workout fad.

Simplifying isn’t about deprivation; it’s about maximizing your enjoyment of a curated selection.

#7: Curate

Own fewer but better things.

Last year I interviewed Jean Chatzky, the financial editor of the Today Show, on the podcast. During our interview, she told me that she only buys items at full price.

Wait, what? She only buys at full price?

Yep.

She realized that when she saw a sale, she would pick up “extra” things — items that she didn’t need, or that she bought impulsively — simply because they were on sale.

- “I wasn’t planning on buying a candle, but it’s on sale for $5…”

- “I don’t need this table, but it’s on Craigslist for $15…”

By only buying items at full price, she owns fewer but better things. Her home is less cluttered, because she’s placed more thought into each purchase.

Lesson:

- A Craigslist sale is still a sale.

- A thrift store sale is still a sale.

- A sale is a sale is a sale.

When you clear out your closet, garage, or attic, the question to ask yourself isn’t, “What should I get rid of?” but rather, “What must I keep? What is so amazing I can’t imagine getting rid of it?”

If an item doesn’t meet that high standard, then why do you have it around? Why surround yourself with mediocre items?

Once you’ve curated your personal possessions down to the few things that matter most, you’ll discover that your desire to spend and accumulate will drop.

#8: Don’t Half-Ass Anything; Whole-Ass the Right Things

Here’s a well-known secret about coupon and deal websites:

Those website owners are successful six- and seven-figure entrepreneurs. They’re promoting money management through shopping clearance sales, but their own finances are fueled by revenue, rather than deal-chasing.

Sure, they might use a $3 coupon on a package of frozen chicken so that they can relate to the content they’re releasing. But on that same day, they might earn $1,000 in daily gross revenue from that same article.

“If you service low-impact activities, you’re taking away time you could be spending on higher-impact activities,” says bestselling author and podcast guest Cal Newport. “It’s a zero-sum game.”

You have time for anything; you don’t have time for everything. Every hour you spend on X is an hour you’re not spending on Y.

- If your toilet needs to be replaced and you decide to install the new one yourself, that’s four hours you’re not spending at the gym.

- If you clip coupons to save $12 per week on groceries, that’s one hour you’re not spending on growing a side business.

What matters most?

#9: Work with Your Nature, Not Against It

A couple of years ago, I decided I wanted to drop the vast majority of my freelancing and consulting clients. I didn’t need the money; I’d gained financial independence, and I wanted to spend my time traveling, writing, and podcasting.

Yet I felt reluctant to cut the cord.

“If only I were more disciplined, I could do both,” I told myself. “If only I were focused, I could keep my freelance/consulting clients while also going to the gym and cooking and traveling and reading and writing and podcasting and making space for a social life.”

I’d take an honest look at my time (including tracking my time in 15-minute intervals) and I’d see how much time I wasted. Fifteen minutes here; 20 minutes there.

“If only I didn’t waste so much time,” I told myself, “I could do it all.”

And then I drove myself crazy trying.

Because you know what? I’m not more disciplined. I’m not more focused. I’m capable of a certain amount of daily output, and that’s that. My mission isn’t to increase my output, it’s to curate what happens during those hours.

Eventually, I admitted to myself: “I can’t do everything. If I want to lead the type of lifestyle that I want to lead, then something’s gotta give.”

That’s when I dropped my clients and lived happily ever after.

Do you tell yourself, “I’d be [X] (happier, more successful, more fit) … if only I had more willpower” or “… if only I was more disciplined?”

You know what? You are who you are. Find ways to work with your nature rather than constantly battling against it.

#10: Focus on Habits, Not Willpower

When I wake up, I immediately drink a glass of water. This isn’t an act of willpower or discipline. It’s because I formed a habit.

“Willpower isn’t just a skill, it’s a muscle, like the muscles in your arms or legs,” says Charles Duhigg, author of the fantastic book The Power of Habit. “And it gets tired as it works harder, so there’s less power left over for other things.”

If you rely on willpower, you’ll eventually get tired and give up. But if you focus on forming habits, willpower doesn’t enter the equation.

Here’s how to turn anything into a habit:

- Find a cue, or trigger.

- Take an action.

- Receive a reward.

My cue or trigger is waking up. The action is drinking a glass of water. The reward is the instant feeling of hydration.

Here’s the part that most people get wrong: the action should be its own reward.

Most people try to set up a system in which they have a cue (I finish my workday), they take an action (I lift weights), and they receive an unlinked reward (I allow myself to drink a glass of wine when I get home).

Author Gretchen Rubin found that unlinked rewards are counterproductive, because you begin to see an activity as a means to an end. If you reward yourself with a blueberry muffin every time you go running, your brain starts to think, “Okay, if I go running, I can eat this blueberry muffin.”

You’re not learning to appreciate running for its own sake. You’re only learning to cope with running in order to get to that muffin.

The more effective approach, Rubin found, is to find the inherent rewards of running, like the “runner’s high” you feel immediately afterward. Focus on this as its own reward.

If you must give yourself an external reward, she recommended, choose something that furthers the activity of running — such as a new pair of running shoes, or a better rain jacket for the days you’re jogging outside during a drizzle.

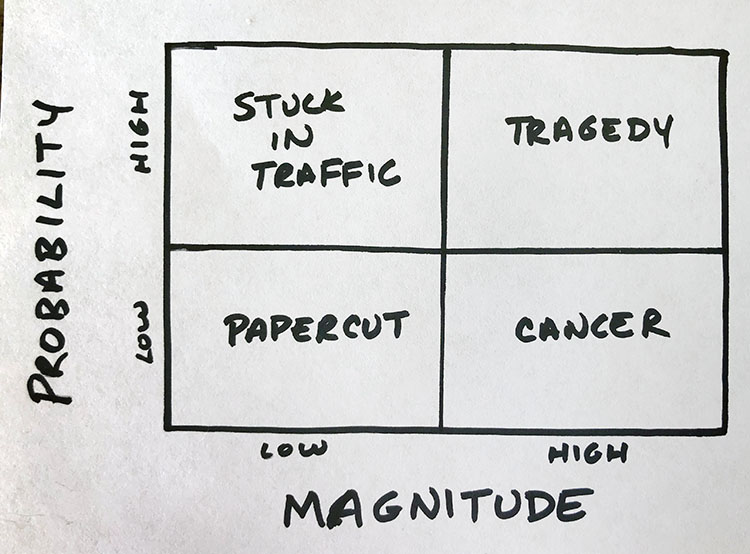

#11: Risk = Probability x Magnitude

“How risky is this?”

I frame the concept of “risk” as the probability that something may happen, multiplied by the magnitude or impact of its consequence.

There’s a low likelihood that I’ll get a papercut today. And if I do, the papercut’s impact on my life will be near-zero. Therefore, the risk of handling paper is low.

There’s a high likelihood that I’ll get stuck in traffic at least once this month. But the impact of a few extra minutes in traffic is unlikely to have a big effect in my life. Therefore, getting stuck in traffic is a low-risk activity, even though there’s a high chance of occurrence.

There’s a low likelihood that I’ll get diagnosed with cancer, but if I am, the impact on my life would be tremendous. Therefore, this is a high-risk situation.

There’s a high likelihood that I’ll experience tragedy during my lifetime. And it’ll be shattering. This is also a high-risk situation.

Prepare (and insure) against the situations that are risky. Don’t stress about the ones that are not.

This framework (risk = probability x magnitude) can help you make smarter decisions. Should you quit your job? What rates should you quote to a client? How much should you offer on that house?

Ask yourself what’s the worst that can happen. Oftentimes, once you start to think through the worst-case scenario, you realize it’s not that bad. Many of the things that scare us are survivable.

#12: Value = Impact x Reach

The value that your work/business creates is the impact you have on others, multiplied by your reach.

If either variable (impact or reach) is high, then your work is high-value, even if the other variable is low.

A trauma surgeon makes a massive impact in the lives of others, yet she concentrates that impact on a relatively small number of people (each patient gets individual attention). She impacts thousands of people, but not millions. Her impact is ultra-high, so the value of her work is high.

In comparison, Coke or Pepsi makes a small impact on people’s lives. We enjoy a fizzy caffeinated drink. But they reach billions of people, and as a result, their value is high.

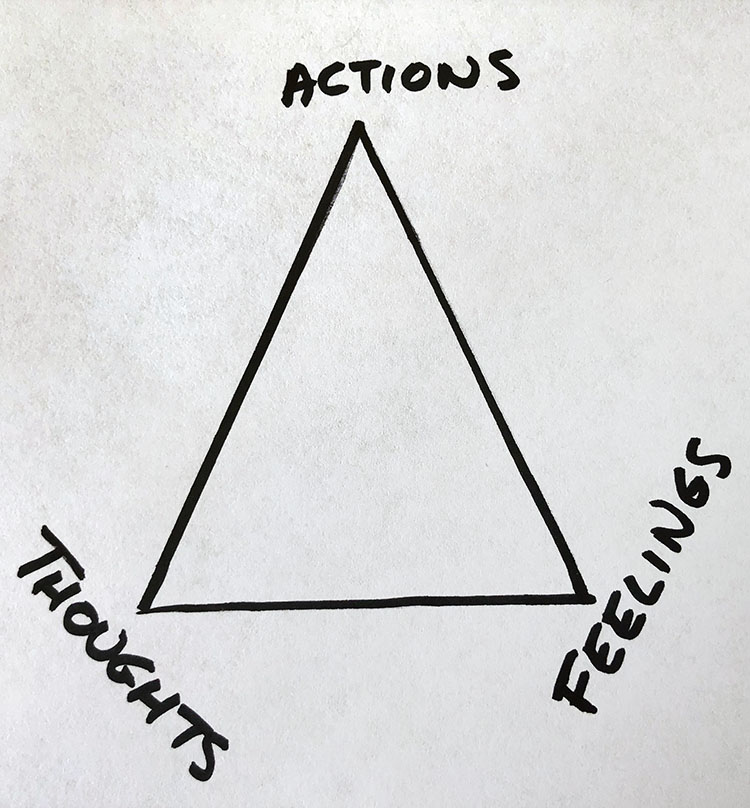

#13: Achieve Being Through Doing

The best cure for writer’s block is to start writing. The best cure for not wanting to exercise is to start moving. You don’t need to feel like doing something before you do it.

Act first, and the feeling will follow.

Thought, behavior and emotion are interrelated. By changing your behavior, you can influence your thoughts and emotions.

#14: When You’re Not at Work, Don’t Be at Work

Here’s a pet peeve:

I’ll go to a party, or meet a stranger in an UberPool, or start chatting with someone at a festival. They open with the question, “What do you do?”

Guess where that leads the conversation? Yep. We start talking about work.

I reply that I’m a podcaster, they ask follow-up questions (like “what topic do you cover?” or “how do you make money podcasting?” or “how did you get into that?”), and soon the conversation starts to mimic high school Career Day.

This is one of the many ways people stay “at work” even when they’re not at work.

Work isn’t everything. When you’re not at work, don’t constantly think and talk about work. You’re not there, so don’t be there.

This is the art of being present.

By the way, I’ve started a new game. If anyone asks, “What do you do?” I respond, “Great question! Okay, here’s a game. I’m going to list three different careers, and you have to guess.”

And that leads to the next lesson …

#15: “Yes, And…”

The most important rule in improv comedy is to “yes, and” the situation.

If another actor says, “My brother is flying to Moscow,” you can’t reply, “You don’t have a brother.” That negates the storyline.

You have to accept the premise and say something like, “Did he accept that job offer from the Kremlin?” This keeps the story moving.

Just like in improv, life gets easier when you take a “yes, and” attitude toward whatever comes your way.

If you’re at a party and someone asks “What do you do?,” don’t push back with, “I don’t come to parties to talk about work.” Your heart may be in the right place — you’re trying not to think about work outside of work — but that kind of resistance puts up a wall and cuts off the conversation.

Instead, be open to what the person is saying and build on it: “Hey, that’s a great question. All right, I’m going to list three things. You’ve got to guess.”

This “yes, and” response takes the conversation to another level — and it’s a heck of a lot more fun.

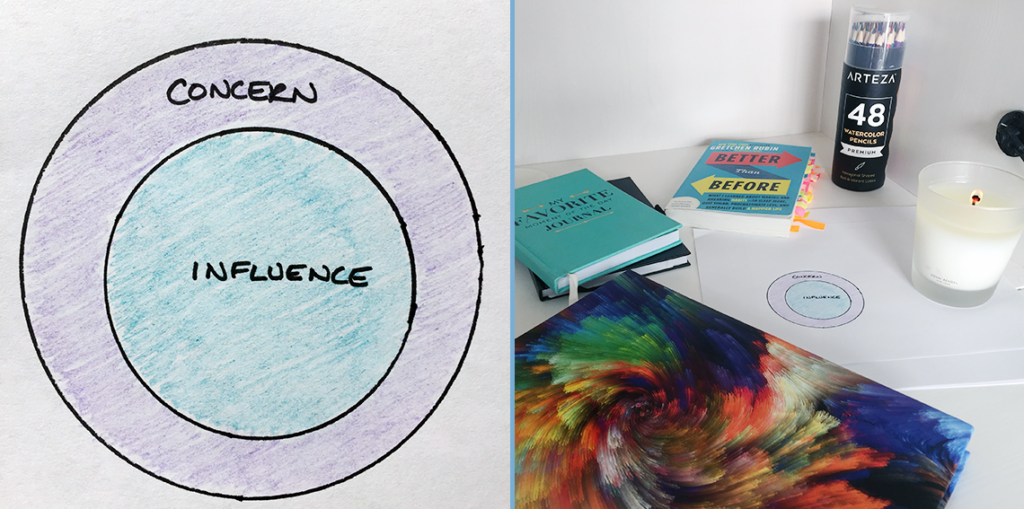

#16: Stay in Your Circle of Influence

In Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey explains this concept by describing two circles. One is called your circle of concern. Inside your circle of concern is everything you could possibly be worried about, from nuclear war to whether or not your socks match.

The other is your circle of influence. These are the things you can directly influence, like whether or not your socks match.

To be effective, focus on your circle of influence. For example:

- You can’t control the stock market, but you can control your contributions.

- You can’t control the job market, but you can develop skills, expand your network, and build a nice stash of “FU” money.

- You can’t control whether or not we find a cure for Alzheimer’s, but you can control whether or not you contribute to the cause.

Stay inside your circle of influence. The more you do, the bigger your circle of influence grows.

#17: What Is Stated Happens (WISH)

If you say, “I’m not a good investor,” guess what? You won’t be.

If you say, “I’m not good at math,” you won’t be.

If you say, “I’m awkward at parties,” you will be.

Our actions follow our words, so be careful about the words that come out of your mouth.

That’s why I don’t believe in the statement, “I can’t afford it.” It’s self-defeating. You can afford anything — not everything, but anything.

Sure, there are reasonable limits. You can’t afford a rocketship to Mars. You can’t afford to single-handedly pay off the national debt of Ghana. But within reason, you can afford anything.

You can travel to Europe for six weeks. You can buy an RV and cruise across the nation. You can save for a downpayment on a rental property.

Try this:

- Replace “I can’t” with “I choose not to.”

- Replace “I don’t have time” with “it’s not a priority.”

“I can’t afford to travel” equals “I choose not to travel because I’d rather [X] — eat at restaurants once a week, drive a 5-year-old car instead of a 15-year-old car, etc.”

“I don’t have time to exercise” equals “It’s not a priority to exercise.”

Anytime you catch yourself saying (or thinking) “I can’t,” reframe this idea. Then ask yourself if the new statement resonates with you. Do your actions reflect your priorities?

If they don’t, it’s time to make a change.