It’s official: I tested positive for coronavirus.

You’ve probably heard people say that if you’re young, healthy and you contract Covid-19, you’re likely to only experience mild or moderate symptoms. I’m 36, a non-smoker, in shape, fit and healthy, with no chronic conditions. No asthma, no diabetes, no cancer, no high blood pressure, no history of any type of organ disease. I’m the poster child, the ideal candidate, of someone who would only experience a “mild or moderate” case.

My experience of coronavirus was sheer brutal hell. It was the most intense prolonged physical agony I’ve ever felt.

Here’s what coronavirus feels like.

Before The Infection

Let’s start at the beginning of March.

Like many people, I’d heard chatter about coronavirus since mid-February, but I’d initially shrugged it off. I’m skeptical of media fear-mongering; it seems “the next big threat” is constantly looming on the horizon, and I’ve long ago learned to tune it out. But the chatter seemed to be growing louder, so I decided some research was in order.

March 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th:

I begin binge-reading articles about coronavirus. I gobble up news from the Washington Post, the New York Times, and a half-dozen other major publications. The more I read, the more I realize that the media is suffering from its “Boy Who Cried Wolf” moment. Yes, they’re guilty of ringing many false alarms in the past. But this time, the wolf is real.

I’m convinced that coronavirus is one of the greatest threats that our society will face during our lifetime, and I become impassioned about doing everything in my power to help flatten the curve. I write an internal company update to my team saying, “I’m obsessed with coronavirus and I think it’s going to affect everything we do for the next few months.”

Friday, March 13:

One of my friends throws a birthday celebration at a local bar. I’m convinced that leaving home would constitute a public health risk. I text one of my friends to say that I’m not coming.

“I know it’s scary,” my friend writes back. “We figured it’s at a small bar with people we know.”

I look at that text and think: WTF? that doesn’t make any sense.

“With people we know?” How is that relevant? Sure, “with people we know” is helpful for not getting murdered, but the degree of familiarity that I have with someone doesn’t affect the likelihood that either they or I will be asymptomatic carriers of a contagious disease.

I skip the birthday celebration. Friday, March 13th becomes the first time I change my plans in order to take an abundance of caution.

Saturday March 14:

Although I feel healthy, I begin self-isolating. I know that people can be asymptomatic but highly infectious for 14 days, and I decide that the safest course of action is to change my default assumptions.

Most people default to assuming that they’re not infected, and they live their daily lives accordingly. That’s why Covid-19 is spreading so quickly.

I decide to change the default. I’ll default into assuming that I have it, and that my goal is not to spread it to anyone else. Likewise, I’ll default to assuming that everyone else has it, and that my goal is not to get infected by them. I make every decision from that premise. This leads me to start my precautionary quarantine, beginning on March 14.

I stop going to the grocery store (I get deliveries from Instacart and Amazon). I stop going to the gym (I work out at home). I work from home normally, so that remains the same. I cancel a dentist appointment and cancel a haircut (and to support the local business, I buy a $200 gift card. My hair is going to look amazing in six months).

I feel perfectly healthy. I don’t know anyone else who is isolating as a precautionary measure.

“Are you feeling sick?,” one of my neighbors asked. “Or have you traveled out of the country recently?”

“Nope, this is what’s required to flatten the curve,” I replied. “This virus is growing exponentially.”

His response politely indicates that he thinks I’m being paranoid. Why on earth would I isolate myself if I’m healthy and haven’t been exposed to anyone who’s infected? I hear this same response from almost everyone I talk to; my social circle all seems to think I’m going overboard.

I don’t care. Let them think I’m paranoid. It’s better than committing manslaughter.

Sunday, March 15:

I’ve taken a hiatus from Instagram since New Years Eve, but I feel a renewed sense of purpose. I’m going to use my platform to spread the message of flattening the curve.

I publish my first IG post in two and a half months, urging people to stay home. I email my team and tell them that I’m going to start dedicating special podcast bonus episodes to flattening the curve.

I’m going to do everything in my power to slow the spread of Covid-19.

Monday, March 16:

I send an email to my podcast show notes subscribers, saying: “After a lot of reading, I am convinced that the coronavirus threat is one of the most serious — if not THE most serious — known threat in our lifetime to date.”

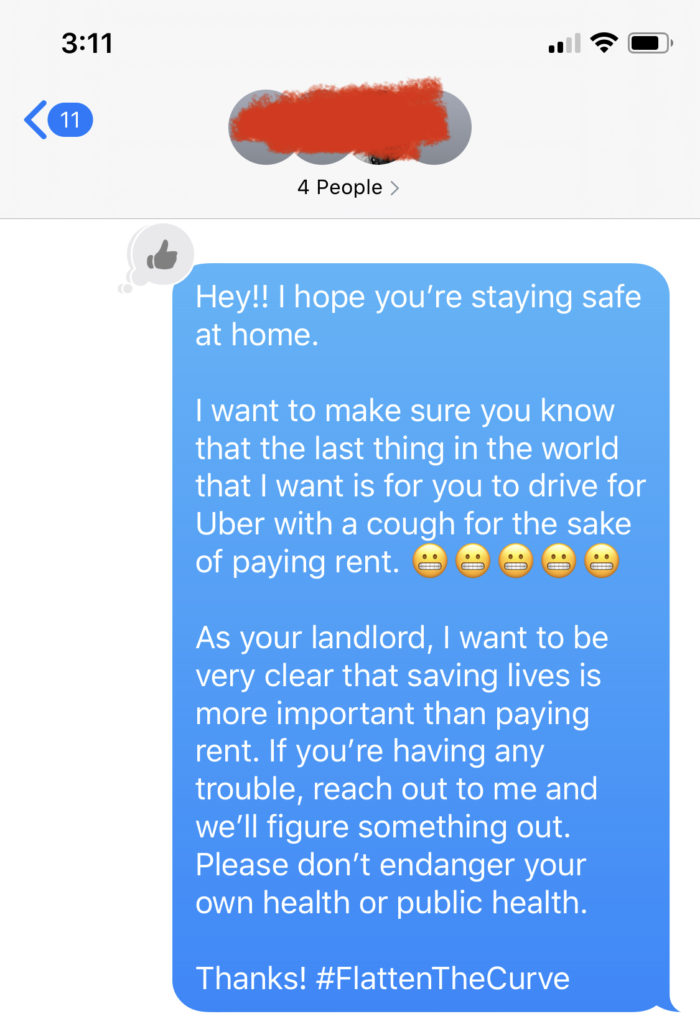

I’m a landlord, and I send my tenants this text message:

Thursday, March 19:

I roll out the first episode of PSA Thursday, a weekly segment on my podcast in which I talk about coronavirus, the stock market collapse, and how to handle life, work and money during a pandemic. I publish show notes that say, “My chief overriding mission is to use this platform to do everything in my power to help slow the spread of coronavirus.”

Friday, March 20:

I start feeling tired. I take a nap in the middle of the day, which is unusual. I don’t think I’m sick; I assume I’m stressed out or sleep-deprived. I go to bed early.

Saturday, March 21:

I feel tired and run-down. I eat an early dinner by myself at home and immediately go to bed, falling asleep around 5 pm. I wake up around 11 pm, look at the clock, and feel surprised that I’ve slept for so long at such an odd time of day. I walk into the kitchen and lean against the counter. I feel groggy and weak. I feel dizzy. And then — boom — I fall.

One moment I’m standing upright. The next moment a wave of dizziness hits me. And the next moment, I’m lying face-down on the hardwood floor, staring at dust and crumbs.

My first thought is of those much-parodied Life Alarm commercials that were popular in the 1990’s, the ones in which an elderly lady says, “I’ve fallen and I can’t get up!” I realize that I’m home alone, I’ve fallen, and suddenly that service makes a lot of sense.

My second thought is knowledge that I’m not hurt. I know instinctively that I’m fine, that I didn’t injure myself in the fall. “I’m glad I’m in my thirties,” I think to myself, “and not in my seventies, when falling could be a death sentence.”

My third thought is that my kitchen floor is incredibly dirty, now that I’m looking at all these crumbs up-close.

I pull myself up, grab a glass of water, and go back to bed.

Sunday, March 22:

My body aches. My head feels like a lead weight. I’m shivering. I’ve been sleeping all weekend, yet I’m exhausted. I lay in bed, realizing that I have a fever. I don’t want to get the thermometer from the bathroom cabinet, because it’s going to confirm what I already know: I’m sick AF.

But I need the data, so after several hours of laying in bed, shivering and feeling like every muscle in my body has been pummeled into oblivion, I drag myself out of bed. The distance from my bed to the adjoining bathroom feels like a thousand miles. I take the thermometer out of the bathroom medicine cabinet and stick it under my tongue.

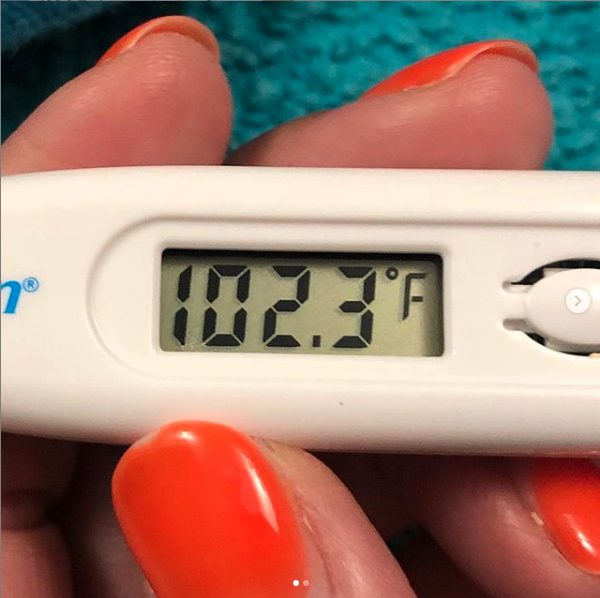

It beeps: 102.3 degrees.

I don’t know if this is coronavirus or if it’s the seasonal flu. I received a flu shot in the fall, but I know that people can still contract the flu, even if they’ve had a flu shot. I don’t have enough energy to think about it. I go back to bed.

Monday, March 23:

I’m utterly drained. The smallest actions require Herculean effort.

I tell myself, “Paula, you’re going to sit up. You’re going to transition from lying down to sitting up.” This task feels overwhelming. I lay in bed and give myself pep talks. “You can sit up. You can do it. Pull yourself up slowly. Sit. Sit.” I delay for an hour, then another hour. The idea of sitting up is too exhausting.

I call my parents and tell them that I have a fever. They advise me to take acetaminophen. I have a bottle of pills, but it’s in the bathroom medicine cabinet, the same place where the thermometer is located. Objectively, this is only about 20 feet from my bed. It might as well be 20 miles uphill in a sleet and hail storm. How am I going to walk that far?

I suffer through the marathon distance from my bed to my bathroom and back again. I swallow 1000 mg of acetaminophen, along with a glass of water. I have zero appetite, but I force myself to choke down some food so that I’m not taking it on an empty stomach.

I don’t want people to know I’m sick yet. I publish an impersonal message on Instagram, urging people to default into assuming that they have it, and that their goal is not to spread it to others.

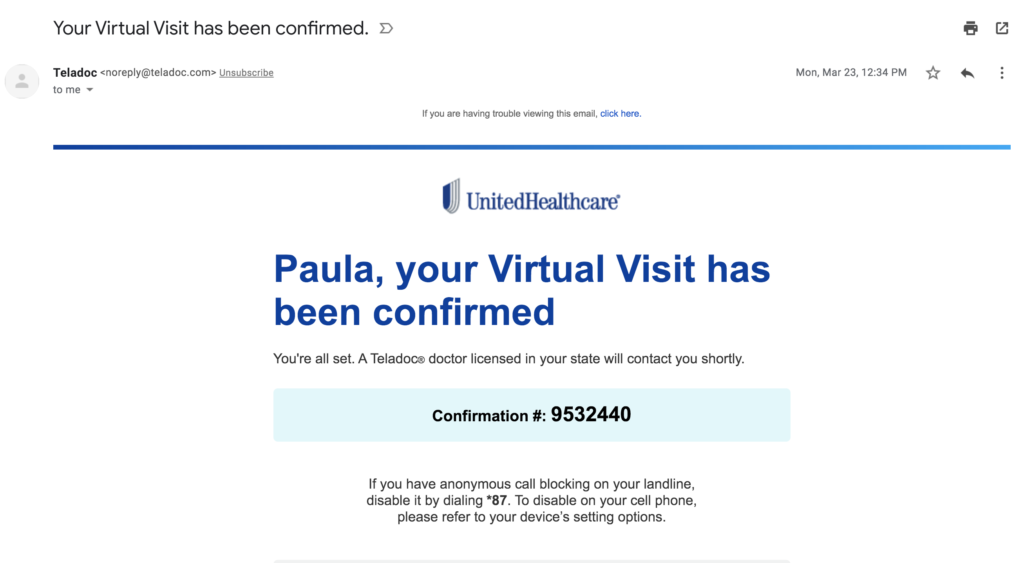

I need to see a doctor, but I can’t drive, and I don’t want to infect other people at a clinic. I open my laptop, visit the United Healthcare website (they’re my insurance provider), and register for a Teladoc appointment. They send me a confirmation email, letting me know that I’m in the queue for a video chat or phone call with a doctor.

I use every ounce of energy to run a Google search for “how to get a coronavirus test in Las Vegas.” Basic tasks, like typing into a search engine or clicking on a link, are excruciating. I read slowly, like I’m just learning how to read for the first time. My head is swimming. I can’t think straight.

I learn that there’s an urgent care clinic administering Covid-19 tests. I use every ounce of energy to send them an email, letting them know that I have a high fever. I ask for a doctor from their clinic to call me, and I ask for a test.

I’m supposed to release a podcast episode every Monday. I have an episode that’s 90 percent complete, but there’s no way that I can carry it to the finish line. I record a short 5-minute announcement for my audience, telling everyone that I have a fever. I report the previous day’s reading, 102.3 degrees, and I clarify that I haven’t been tested, so I don’t know if this is the seasonal flu, a random fever with terrible timing, or coronavirus.

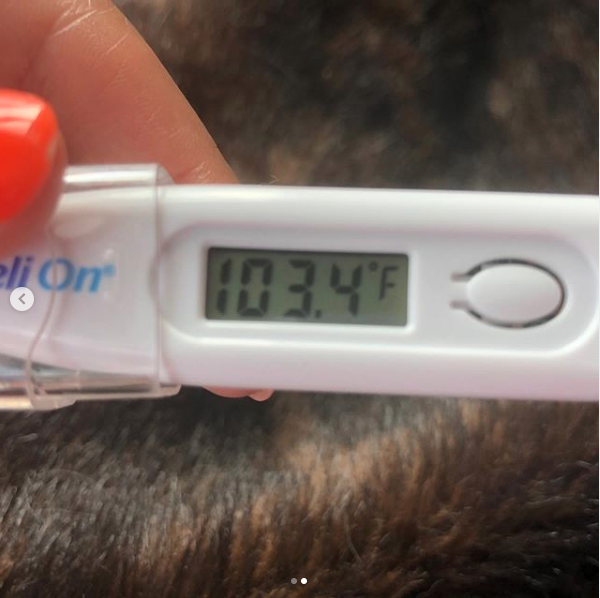

I spend the rest of the day shaking, shivering, aching, and feeling like every ounce of energy has been drained from me. I continue taking 1000 mg of acetaminophen every six hours. I sweat buckets for an hour or two, and then I shiver and get chills and I know my fever is spiking again.

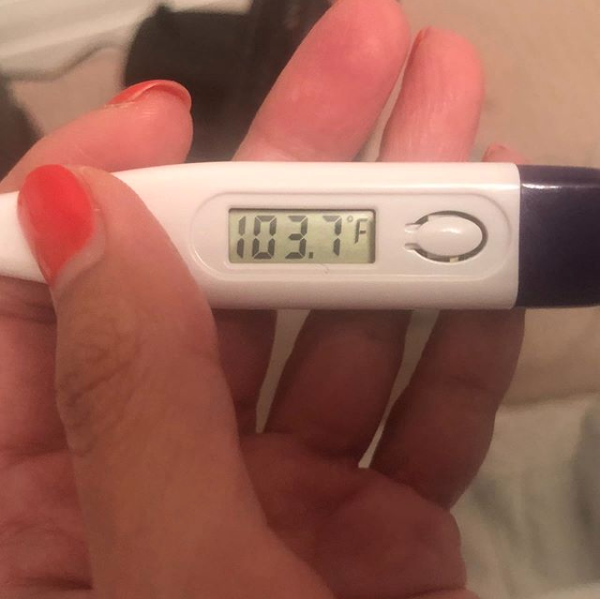

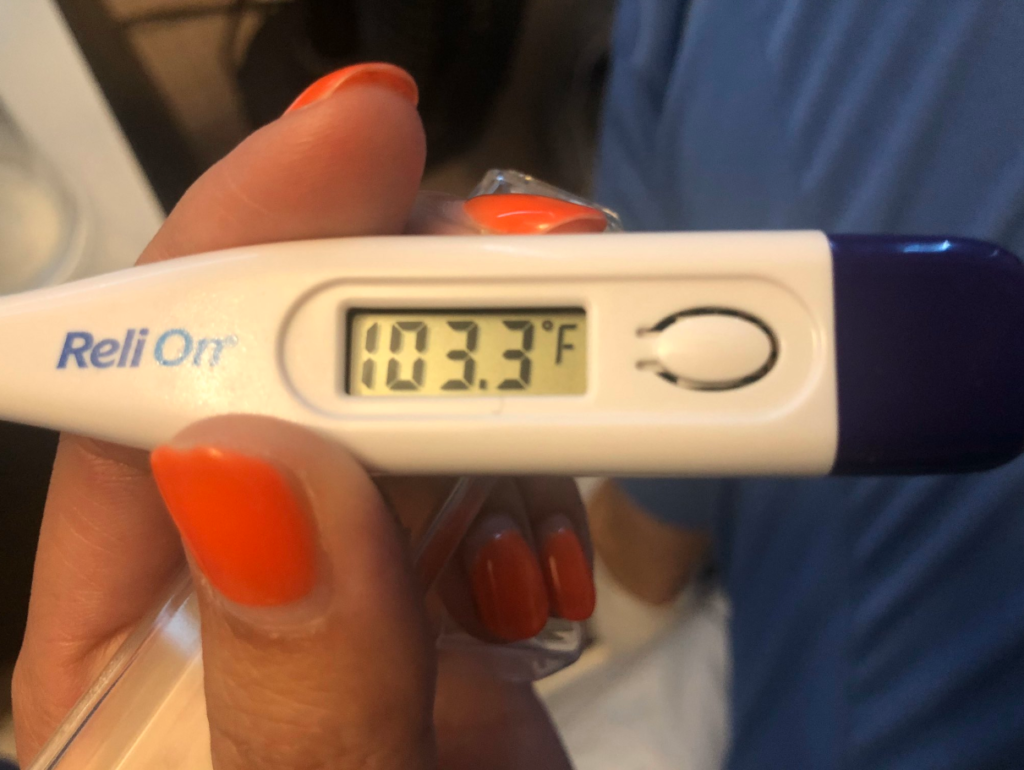

My fever climbs to 103.4 degrees. I take a photo of the thermometer and post it on Instagram, with the label “Quarantine Day 10.” I hope the message encourages people to stay home, to quarantine as a precaution, because none of us know if we’re infected or not.

Thank goodness I quarantined as a precaution. There’s a decent chance I’ve got the rona.

Tuesday, March 24:

My fever spikes to 103.7 degrees. My ears are ringing. My head feels like it weighs a thousand pounds. I can’t move. I’m seriously afraid that I might lose my mind, that I’ll need to call 911 on myself but that I won’t have the mental capacity to do so.

I text my neighbors, letting them know that I’m extremely sick. I tell them that I’ll text them at least three times a day, and if they don’t hear from me with that level of frequency, they should call emergency services, or ask the front desk staff of our building to force their way into my unit. (The front desk staff has a key to every unit.) I tell them that it’s likely to be Covid-19, so take every precaution. I’m a living contagion. Nobody should be near me. I’m scared I might die alone.

I get an email from Teladoc. It says the following:

No explanation. Nothing. I can’t get an appointment with a doctor, and I don’t know what to do next. I don’t have the capacity to think about who else to talk to, how to manage my own care. My head is splitting in agony. My body hurts. I’m alternately shivering, then sweating buckets, then shivering again. I feel like a lead weight is on me.

I get a text message from the urgent care clinic. It says the following:

Great. Two leads, both went nowhere. I have no idea where to find a doctor, how to get a test, how to get any help at all. My parents tell me to call an ambulance, but I don’t think that my symptoms are bad enough to merit that. But there’s no way that I can drive myself to an urgent care clinic. And I certainly can’t ask anyone else to drive me; I’m infectious. My attempts at getting a phone call with a doctor failed, twice. I’m stuck and I can’t get any care.

I take more acetaminophen. I’m taking 1000 mg every six hours. I worry it’s too much, but I’m trying hard to keep my fever below 104 degrees. I’m worried that the high temperatures might be permanently damaging my brain. Can that happen? I don’t know. It feels like it can. My brain feels like mashed potatoes.

My neighbor sends me a text, letting me know that the University of Nevada, in conjunction with a local urgent care clinic, is administering Covid-19 tests. He sends me the phone number. I call. The woman who answers the phone asks me if I’m experiencing any chills. “I have a fever of 103.7 degrees,” I reply. She tells me to come to the drive-through clinic at 2 pm tomorrow. Victory! I’m finally going to get to talk to a medical professional, tomorrow, maybe, I hope.

I have no energy, but I force myself to get out of bed and leave out a months’ supply of food and water for my two cats and my turtle. If I’m incapacitated, at least they won’t starve or dehydrate.

Wednesday, March 25:

My fever is 103.3 degrees. The acetaminophen will sometimes drop the fever temporarily, down to the 100 – 101 zone. There’s a moment when it hits 99.4 and I feel relief, like maybe I’m not frying my brain.

I sweat buckets, wake up with soaked clothes and soaked bedsheets, drenched in sweat from the fever breaking. I try to change my clothes frequently, so that I’m not wearing sweaty clothes. I have a huge stack of old t-shirts that I’d been meaning to throw out. Thank goodness I didn’t. I wear through them in rapid succession. Changing my clothes requires an excruciating level of effort. It’s my biggest activity for the day. I can’t remember the last time I brushed my teeth. Who has that kind of energy?

I start coughing. I’ve only had a mild cough until this point. But now it escalates to serious. I’m coughing harder than I’ve ever coughed in my life. I dissolve into coughing fits that take over my entire being.

I cough so hard I’m seriously afraid I’m going to fracture a rib.

I’m nervous about driving to take the Covid-19 test, but the premise of drive-through testing is that sick people have to get behind the wheel. The only way to get a diagnosis, and to talk to a doctor, is going to involve getting behind the wheel. I spend the morning bracing myself for this challenge, giving myself pep talks.

Half an hour before the appointment, and just minutes before I was about to get into my car, I get a phone call from the testing facility. They’ll have to delay my test until tomorrow.

“Is there any chance I can take it today?” I beg. I still haven’t been able to talk to a medical professional. I’ve spoken to nobody about my symptoms. I’m desperately trying to get a call with someone, but every road I pursue turns into a dead-end.

“Nope, sorry, we’re over capacity,” the person tells me, and hangs up.

I take more acetaminophen. I have no appetite, but I soak Belvita breakfast tea biscuits in water until they’re soggy and then force myself to swallow them, so that I can have at least a little food in my stomach.

Thursday, March 26:

My fever is 102.7 degrees.

It’s drive-through testing day, and I spent the morning praying that they don’t cancel at the last minute like they did yesterday. I need to get tested. I need to talk to a doctor. I can’t find any help.

I’m alone in my condo, and sitting up is painful. I feel best when I’m laying down, but I know that every few hours, I need to drink water, I need to take more acetaminophen, I need to soak a biscuit in water and then swallow it so there’s some food in my stomach. But all of it is so hard. Sitting up is painful. Doing anything at all, even using the toilet, is the most draining task imaginable.

Somehow, miraculously, I manage to drive (extremely slowly) to the urgent care clinic that’s administering Covid-19 tests. There are big handmade signs out front telling me to keep my windows rolled up. I pull into a parking spot. Someone in a mask in the parking lot approaches and asks me if I have an appointment. I nod. He tells me to wait.

Forty-five minutes pass by. I can feel my fever spiking again. I know because I’m shivering. I start the car, turn every vent towards me, and blast the heat at maximum capacity. I’m still shivering.

Someone finally asks for my name. I tell him, and he says he can’t find my paperwork. Through heaving dry coughs, I tell him that I was supposed to get tested the previous day; my documents might be filed there. He disappears for 15 minutes, then comes out and says that I’m registered for a 4 pm appointment. I was told to come at 2 pm by the scheduling person on the phone, although by this time, I’ve been waiting so long that it’s already 3 pm. He says he’ll test me right now, since I’m here.

A different guy comes out. He sticks a swab up my nose. When I say “up my nose” — this swab travels further than I knew was possible. I now have a new understanding of my face. Visualize someone sticking a swab as far up your nose as you could possibly imagine. Then imagine it going even further than that. The test is awkward and uncomfortable, but I’m happy to finally get tested.

As I’m shivering and coughing in this parking lot, my phone rings. It’s a medical professional who works at the urgent care clinic. FINALLY! For the first time, I’m able to talk to a licensed professional about my symptoms. I’ve already been sick for 7 days at this point, with a confirmed fever for 5 days.

I describe the fever, ranging from 102.3 through 103.7 degrees and lasting through the entire week. I tell her I’m coughing so hard I’m afraid of fracturing a rib. She asks for my height, weight, health history. She tells me to keep taking acetaminophen, to avoid ibuprofen, and she prescribes me an albuterol inhaler and promethazine, a cough suppressant.

I drive home in a daze, shivering. When I arrive back at my condo, I’m too cold to leave the car. The air vents are still pointed at me, blasting hot air at maximum capacity, and I can’t leave the comfort of that heat. I’m shivering too much, my chills are too severe.

I sit in a parked, running car in my parking garage for about 30 minutes, shaking and shivering. Then I gather all my energy, step out of the car, and brave the chills while I head up to my condo unit.

Once I’m inside, I take a long, steamy shower with the water at maximum heat. I shower for about 30 minutes, and when I come out, I’m still shivering. I lay in bed with piles and piles of blankets on top of me, shivering. My fever spikes again.

Friday, March 27:

My fever is 102.8 degrees. I ask a friend to pick up my prescription for me. I hurt. Everything hurts. I can’t get out of bed. Sitting up is difficult. Using the toilet is difficult. Walking hurts.

I get winded by doing anything. Talking. Walking from my bed to the sink. I get winded taking a few steps.

I’m running out of dishes. I live alone and I haven’t been able to clean any dishes for the past week. All my water glasses, dirtied with Propel electrolytes that I’ve been adding in there, are scattered throughout the condo. I can’t handle it. The smallest tasks, like just pouring myself a glass of water, consumes all my energy for the day. I keep a jug of water next to my bed, but I don’t have the energy to sit up and sip.

Saturday, March 28:

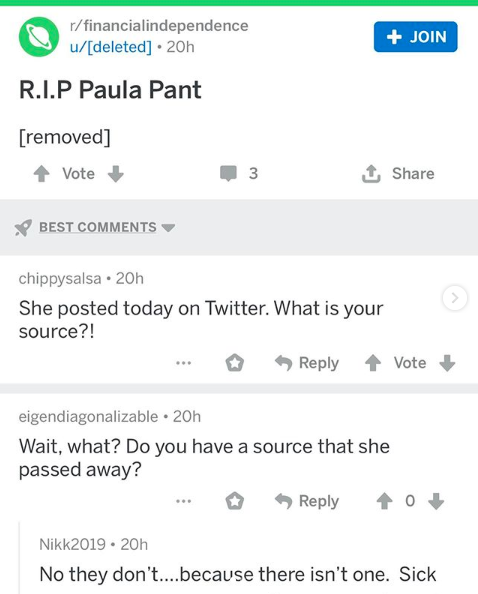

There’s a rumor on Reddit that I’m dead. I get a notification of a Google News Alert, with a headline that says “RIP Paula Pant.” It links to a Reddit thread in which someone is eulogizing me. It’s surreal.

I take a screenshot and post it to Instagram, issuing the following clarification: “Rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated.”

My fever drops to 100.9 that morning. That’s the lowest it’s been since Sunday. I take some more acetaminophen. I’m coughing hard. The cough medicine doesn’t seem to be doing much, and I don’t understand how the inhaler is supposed to help. I take both regularly — the inhaler every four hours, the cough medicine every six hours — but I’m still coughing harder than I could ever describe.

Sunday, March 29:

I’m fever-free for the entire day! But my body aches, I’m exhausted, I’m sleeping 18 hours a day, and I’m coughing harder than I knew was possible. I’m terrified that I might have pneumonia.

Monday, March 30:

I get a phone call from urgent care. “Your test came back positive for Covid-19,” they tell me. It’s confirmation of what I already knew. They prescribe a different cough medicine, Virtussin, and advise me to stay at home and not go to the hospital unless I have shortness of breath.

I Google, “what is shortness of breath?” I get winded at the slightest thing. Does that count? I feel like that’s not enough to justify going to the hospital. I decide that I’ll seek help if I get winded while I’m sitting or lying down.

Tuesday, March 31:

I’m exhausted. The smallest things, like pouring a glass of water, are utterly draining. I’m sleeping 18 hours a day. But I’ve been fever-free since Saturday. That’s a huge victory. That said, I’m still more sick than I’ve ever been in my life.

Wednesday, April 1:

All I do is lay down, sit up, cough, drink water, force myself to have soup and smoothies, and lay down some more. I’m coughing hard.

Thursday, April 2:

I’ve been fever-free since last Saturday. I’m drained. I’m coughing constantly, but I’m no longer fracture-a-rib level coughing. I feel like a truck full of sawdust has been dumped on me. My bones are tired.

Friday, April 3:

I see an email from my lawyer. There’s someone I’ve been having a legal dispute with. They want a bunch of documents, and they’re threatening that if I don’t provide it by Tuesday, April 7, they’ll escalate in court. My lawyer told them that I have Covid-19, and they wrote back a letter acknowledging that they know about my illness, and then reiterating their legal threat of escalation if I don’t meet their unilaterally-set, arbitrary deadline of April 7th. I’m angry. I’m furious. How could someone be so monstrous as to threaten a sick person? This is the worst of humanity. This is repugnant, abhorrent, evil. The level of narcissism and greed is unimaginable. This is what happens when an abusive, domineering, bullying personality decides to hide behind a lawyer.

The anger spikes my cortisol, and I’m quickly exhausted. I realize that dealing with the stress of this evil bully is only going to make me sicker. I’m coughing harder than I can describe. My head feels like a lead weight. My muscles ache. I try to sleep but the stress of this narcissistic bully keeps me awake, which makes me feel ill. I take more cough medicine with codeine, and eventually sleep comes. I wake up in coughing fits, my chest heaving with coughs. My entire being feels like it’s been run over by a dump truck. I’m exhausted.

Saturday, April 4:

Same. My body is aching. Every muscle feels like it’s been pummeled into oblivion. My brain is gooey, I can’t think straight. I’ve been fever-free for a week, so I know I’m on the mend. But my body is exhausted from fighting a high fever for so long. I get winded walking around my living room.

Sunday, April 5:

I keep taking my inhaler and prescription cough medicine with codeine. I can feel it helping. I’m still coughing, but I’m not in danger of fracturing my ribs anymore. I can’t walk much without getting winded, but I can sit upright. I don’t need to be laying down all the time, I’m good with sitting. My head is still swimming but my ears have stopped ringing, and on the whole, I can tell I’m on the mend.

I fill out a form with the Red Cross, volunteering to donate my plasma once I’m symptom-free for at least 14 days. I know that means I’ll need to wait for more than two weeks, since I’m still showing symptoms, but at least now they have my information. The process has begun. I want to donate my antibodies to protect or heal others, if possible.

This is what Covid-19 feels like. This is a moderate case.

I didn’t have to get hospitalized. I didn’t have to get assistance in breathing. I had a high fever and a cough, and I rode out my symptoms at home, without physically going to a clinic or hospital, without physically being in the presence of a medical professional other than to take the Covid-19 test. By all accounts, this is a moderate case.

And it’s hell. It’s excruciating. It’s brutal.

I’m here to send this message to millennials and Gen Z: don’t dismiss the threat of Covid-19 by reasoning that your experience of it, if contracted, will be “mild or moderate.” Because yeah, sure, it might be. Mine was. I’m young and healthy and had a moderate case. And a moderate case is HELL.

Please stay at home. Wash your hands like you’ve just chopped jalapenos and you need to take your contacts out. Don’t rationalize going out. Don’t assume that you’ll be okay if you’re infected. Take care of your friends and neighbors. Make sure the elderly and immunocompromised people in your communities have people who are delivering items to them, people who are looking out for them.

And don’t assume that your own youth or health is a get-out-of-coronavirus-free card.

Social distancing is a powerful act of social solidarity. Together, we can defeat this virus. Together, we can flatten the curve.