It’s an old familiar hum:

Every January, we kickoff the calendar year with New Years Resolutions: lose 10 pounds, make smarter investments, create an extra $1,500 per month on the side.

Yet by February, we’ve returned to life as usual. The discarded New Years Resolution has become a tired cultural trope.

We blame ourselves for these failures:

- “I should work harder.”

- “I should be more disciplined.”

- “I should stop procrastinating.”

But what if we’re approaching this in the wrong way? What if goal-setting itself is the problem?

Society says goal-setting is as integral to life as food, sleep, and arguing with your GPS.

“Dammit, Siri, I can’t turn left! That’s a one-way street!”

I’ve set countless goals over the years; I’ve achieved some, fallen short at others, and exceeded a few. Yet I’ve also lived with constant, low-level anxiety about my ability to meet my own expectations.

Lately, as a thought experiment, I’ve started wondering what would happen if I gave up the practice of setting goals.

Would I transform into a couch-and-potato-chips sloth, watching cartoons all afternoon? (Actually, that sounds kinda nice.) Or would I relax, and, paradoxically, accomplish more as a result?

I don’t have all the answers, but I’d like to explore these questions. So today, let’s examine the downside of setting goals. We’ll define a “goal” as a specific future outcome (result) that a person or group tries to create.

Problem #1: Goals harm intrinsic motivation.

Imagine your goal is to lose 10 pounds. You exercise daily, but you don’t enjoy your time at the gym. You grudgingly endure your workouts, while fantasizing about results.

What are the chances that you’ll (#1) reach your goal, and (#2) maintain a lifelong exercise habit?

Not likely.

But why?

To answer this, let’s look at two types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic.

- Intrinsic motivation is driven by enjoying the activity itself.

- Extrinsic motivation is driven by an outcome.

If you read books, play guitar, or hike for its own sake — with no expectation of reward — you’re intrinsically motivated.

But if you read books to appear smarter, play guitar to make money or attract dates, or hike to build muscle, you’re extrinsically motivated.

Intrinsic motivation is more effective, research shows. Given the choice between rewards vs. enjoyment, you’re more likely to do stuff you love. For example, students who enjoy learning for its own sake — who are driven by curiosity and challenge — are more likely to remain life-long learners than students who are merely motivated to get a high G.P.A.

Most of us structure our lives and businesses around getting results — “I want to make $500 per month on the side.”

But we’re happier and more productive when we focus on enjoying the activity itself — “I love the challenge of growing a small business.”

Let’s return to our earlier example: your weight-loss goal and subsequent grudging-trips-to-the-gym.

Research shows (and workout enthusiasts know) that exercise is brimming with inherent benefits: lower stress, higher endorphins, better sleep. But if you’re preoccupied with the scale, you might overlook these intrinsic benefits. You’ve re-framed exercise as a means to an end, a delivery vehicle for results, rather than as an activity meant to be enjoyed for its own sake.

You’ve approached it with a results-based mindset (“what can I get from this?”), rather than an intrinsically-motivated mindset (“do I enjoy this?”) And ironically, you’re less likely to achieve and maintain results in the long-term.

The problem gets worse when we start tying “unnatural” rewards to an activity — like rewarding a trip to the gym with an indulgent hour of television.

Bestselling author Gretchen Rubin, in her book Better Than Before, uses this example:

“If I tell [my daughter] that she can watch an hour of TV if she reads for an hour, I don’t build her habit of reading; I teach her that watching TV is more fun than reading.”

Tying an action to a reward is counterproductive.

Rubin, a guest on my podcast, pointed out another problem: goals and rewards create a “finish line.” This undermines the activity by framing it as temporary; it defines a stopping point. Sure, you’ll train for a marathon, but will you continue running once it’s over?

Problem #2: Goals can make you miss the bigger picture.

In the 1960’s, Ford Motor Company noticed that small, inexpensive vehicles had begun booming in popularity.

They wanted to get on the bandwagon. (Is that a pun?)

So the company’s CEO declared an ambitious goal: by 1970, Ford would produce a vehicle that’s “under 2,000 pounds and under $2,000.” (That’s $12,559 in today’s dollars.)

Ford’s engineers and designers threw themselves into this project, and by September 1970, the company started production on its latest innovation: the Ford Pinto.

There was just one tiny problem.

The goal “under 2,000 pounds and under $2,000” was too specific; it didn’t address critical issues like quality or safety. The company’s management, distracted by their narrow goal, overlooked a serious design flaw related to the positioning of the fuel tank: the Pinto could ignite upon impact.

At least 53 people died in Ford Pinto fires, and in 1977, the Pinto became the largest product recall at that point in history.

When Ford’s management focused on a goal that was too narrow and specific, they blinded themselves to the bigger picture.

Conventional wisdom says that goals ought to be S.M.A.R.T. — specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound. For example:

- “I want to earn $10,000 per month by July.”

- “I want my business revenue to grow 15 percent by December.”

- “I want six-pack washboard abs by August.”

“Under 2,000 pounds and under $2,000 by 1970” is a textbook S.M.A.R.T. goal — and on the surface, the team succeeded in reaching this goal.

But this implicitly relegated other qualities, like safety, to — um — the backburner. (Oohhh, no pun intended.)

(Ouch, that’s terrible.)

The Ford Pinto case study, while an extreme example, is a cautionary tale: when we set specific goals, we narrow our attention — and therefore we risk overlooking something important.

“Goals focus attention … This intense focus can blind people to important issues that appear unrelated to their goal,” wrote a team of researchers in a Harvard working paper, Goals Gone Wild. (Yes, that’s actually what they called the paper. Legit.)

“… Consistent with the classic notion that you get what you reward, goal-setting may cause people to ignore important dimensions of performance …,” they wrote.

It’s easy for people (not just companies) to make the same mistake.

When we commit to tight, specific goals — “I’m going to save $1,000 this month!” — we risk creating unintended consequences in other arenas.

For example, have you ever skimped on your health — e.g. eating cheap food like Ramen noodles, or skipping doctor’s visits, or not filling a prescription — for the sake of hitting your savings goal?

Have you ever let friendships, sleep and exercise slide because you’re too focused on a work or business goal?

Yeah, me too.

“What gets measured, gets done,” is a famous quote in management circles, but let’s remember its corollary: what doesn’t get measured gets overlooked.

Problem #3: Fear interferes.

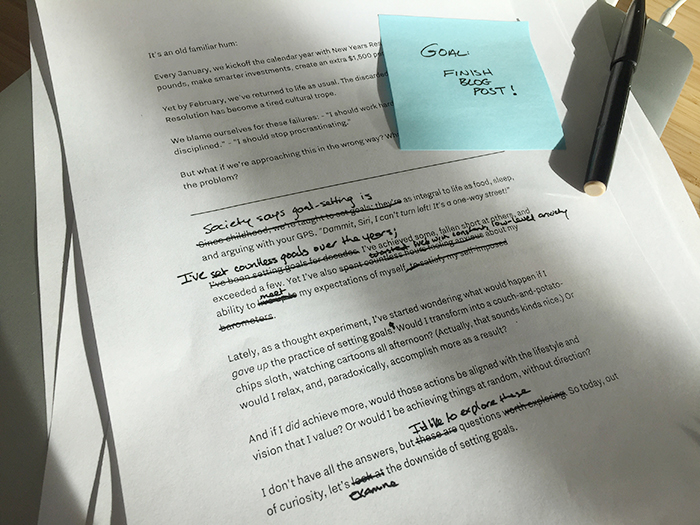

I’ve been trying to write this article for two months.

But procrastination keeps getting in the way. I tell myself that I need to check email. Update Facebook. Buy cotton Q-tips on Amazon.

Then I catch myself. I disconnect from wi-fi; I open my writing program. And … I suddenly need a snack.

At this rate, I’ll speak fluent Portuguese and hold a pilot’s license before I finish this damn article.

If I’m honest with myself, I’m procrastinating because I’m afraid of the outcome.

- What if nobody reads this article?

- What if people read it … but hate it?

- What if I’m a sucky writer?

Procrastination is rooted in fear: fear of failure, fear of success, fear of change. These are rooted in developing an attachment to a specific outcome — another word for “goal.”

As Ray Williams writes in Psychology Today:

“One inherent problem with goal-setting is related to how the brain works. Recent neuroscience research shows the brain works in a protective way, resistant to change. Therefore, any goals that require substantial behavioral change, or thinking-pattern change, will automatically be resisted.

“The brain is wired to seek rewards and avoid pain or discomfort, including fear. When fear of failure creeps into the mind of the goal setter, it becomes a ‘demotivator,’ with a desire to return to known, comfortable behavior and thought patterns.”

Goals trigger fear, and fear gets in the way of the work.

Fear interferes.

In this example:

- I created a goal: write a smart, funny article that my audience will love.

- I developed fear around any other possible alternative. (What if this article is not smart/funny/loved?)

- Fear manifests as procrastination …

- … and this article lives in ‘draft’ mode for two months.

Alternatively, what if I’d told myself:

- I’ll enjoy reading and writing about a fascinating topic.

- Then I’ll share that writing with the world.

If I gave up goal-setting, fear would become irrelevant.

Problem #4: Goals make you dissatisfied with the present moment.

One final objection: Goals are built on the premise that now isn’t good enough.

You’ll be happy later — after you start earning more, after you quit your job, after you can live on your passive investment income.

Goals fixate on the future. If you’re too goal-oriented, you risk missing the present moment; you live for the next milestone.

Again, I’m just exploring this idea. I’m not a card-carrying member of the Anti-Goal League; I’m not making definitive statements. But I’m intrigued enough by the idea of a goal-free existence that I decided to dedicate an article to exploring it.

We’ve outlined the objections above. Now what? Where do we go from here? If goals are flawed, what’s the better alternative? I scoured the Internet and found three options:

Alternative #1: Abstinence

You could avoid goals entirely.

That’s the approach Zen Habits author Leo Babauta embraced, when he declared — (mostly) unambiguously — “I live mostly without goals.”

Here’s how he describes goal-free living:

“What do you do, then? Lay around on the couch all day, sleeping and watching TV and eating Ho-Hos? No, you simply do. You find something you’re passionate about, and do it.”

He says he plunges into activities — such as writing and teaching — without any specific goal in mind. He doesn’t have ‘sales goals’ for his books; he just writes.

Hmmm. I like that. But …

My self-identify as a Type A entrepreneur is kicking up serious resistance. I’m not ready for a goal-free existence. It’s too extreme of a leap — like a steak-and-seafood enthusiast suddenly turning vegan.

What else is on the menu?

Alternative #2: Moderation

On one hand, goals can narrow our focus, dampen our intrinsic motivation, and diminish our enjoyment of the present moment.

On the other hand, goals can inspire, motivate and improve our lives.

Maybe, then, we don’t need to eradicate goals. We need to create better goals.

“Just as doctors prescribe drugs selectively, mindful of interactions and adverse reactions, so too should managers carefully prescribe goals,” wrote the researchers in Goals Gone Wild.

Okay, great. But how?

Alternative #3: Re-Direction

This is the best answer I’ve discovered so far —

Focus on actions, not results.

Instead of: “My goal is to lose 10 pounds.”

Try: “My goal is to exercise daily, cut back on sugar and alcohol, and eat more veggies.”

It’s a subtle difference, but in the latter example, you’re not trying to achieve any results.

If some natural consequence (like weight loss) stems from your actions, that’s fine — but that’s not the point.

You have no expectations, no self-imposed barometers. You’re only thinking about your actions. The results are outside of your control. You won’t be disappointed if a specific result doesn’t unfold; you won’t cross a ‘finish line’ if it does.

Here’s why this is brilliant:

Circle of Concern vs. Circle of Influence

Here’s a circle.

Everything you care about lives inside this circle — nuclear war, terrorism, sustainability, animal rights, the greying of your hair, your minor back pain, those scratches on your car, your investments, your income, augmented reality, colonizing Mars, whether or not artificial intelligence will kill us, and whether or not your socks match.

It’s quite a circle.

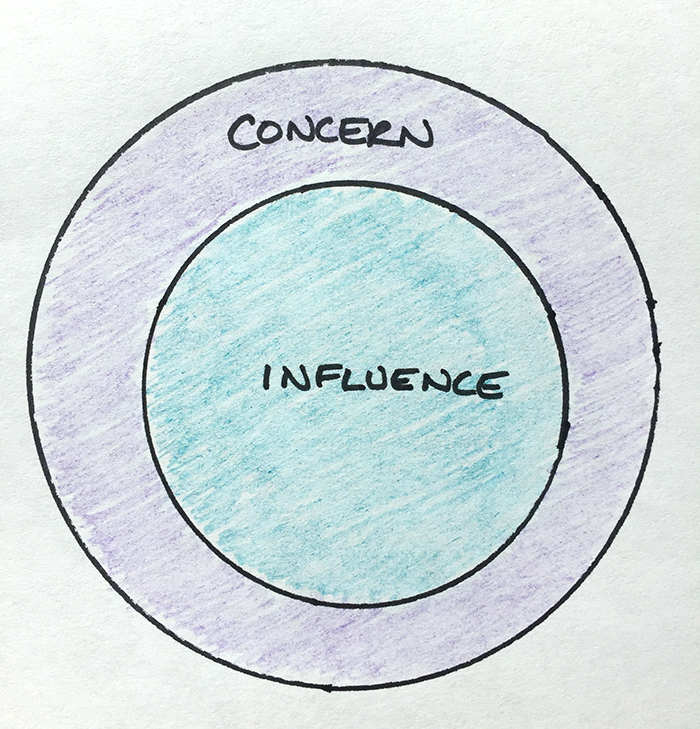

Stephen Covey, who introduced this concept in 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, calls this your “Circle of Concern.” Wallowing within your Circle of Concern creates blockage, resistance, fear. You can’t control these outcomes, so worrying is ineffective.

Inside of this, however, lives a smaller circle.

This circle only holds the concerns you can directly affect. This is your Circle of Influence.

You don’t hold much power or influence over Mars colonization and the future of artificial intelligence. You are, however, the CEO and Chairperson over your investment choices, your focus and effort at developing new skills, your hair color, and whether or not your socks match.

If you operate within your Circle of Influence, you’ll make the biggest impact. And the more you operate inside of this circle, the larger this circle grows over time.

How does this relate to goal-setting? Simply stated:

You cannot control results.

- I can create an online course, but I can’t control whether or not people are interested.

- I can create a podcast, but I can’t control whether or not people will listen.

- I can be kind to others, but I can’t control whether or not people will like me.

Results are outside of your Circle of Influence. But actions are inside of your circle.

- I can create an amazing course. (Actions: outline, research, edit, edit, edit, tear up, re-write, edit.)

- I can prepare for the podcast. (Actions: research guests, prepare for interviews, etc.)

- I can be kind to others. (Actions: for starters, just don’t be a dick.)

I can’t control the consequences. All I can do is act.

This brings us back to the original question: How can we apply this framework towards setting better goals?

Here are a few examples:

Instead of: “My goal is to retire in 10 years.”

Try: “My goal is to invest at least 50 percent of my income into index funds and rental properties.”

Instead of: “My goal is to earn $X this year.”

Try: “My goal is to identify three things that I’m doing that are a waste of time. Then I’d like to redirect this time to something more valuable.”

Instead of: “My goal is to learn basic Spanish.”

Try: “My goal is to use a Spanish language-learning app for at least 20 minutes a day.”

Instead of: “My goal is to write a book.”

Try: “My goal is to read and write from 9 am to 11 am.”

This is a low-stress approach. You cannot fear failure, because you’ve surrendered the results. Your only goal is to act.

As fear subsides, you’re more likely to quit procrastinating. You won’t distract yourself as much with email, Facebook, and buying Q-tips on Amazon.

But you’ll still argue with your GPS.

Some things never change.