Today is the 20th anniversary of the day I learned I was adopted.

On the afternoon I learned the news, I sat in a beige office in a government building.

My dad sat to my right; my mom was perched to my left. An Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) bureaucrat sat on the opposite side of a large, paper-strewn desk.

The INS official was brunette. Young-ish. That’s all I recall about her.

I was there to get my U.S. citizenship. I was too young to understand what “citizenship” meant, though I had a vague sense that it was somehow important. My parents explained that it was a process I needed to undergo in order to reserve my right to vote.

I only knew that my immigration hearing allowed me to escape my 4th-grade math class. If citizenship entails an afternoon without fractions, bring it on.

I’d later learn that most citizenship applicants must pass a civics test filled with questions like, “What’s the introduction to the Constitution called?” (The Preamble.)

I escaped that requirement through a loophole: I was a dependent child. Both my parents swore their oath when I was 8 years old, granting me the privilege to follow suit within a few months. The INS scheduled my naturalization to take place on October 19, which coincidentally happened to be my 9th birthday. (I turn 29 today.)

I was thrilled to ditch school on my birthday, even if it meant I had to spend the afternoon in a featureless office in downtown Cincinnati.

The brunette bureaucrat handed us a thick stack of papers. The grown-ups pored over documents while I daydreamed about ice cream. Hours passed, but I didn’t mind. Immigration hearings are more fun than long division.

Then the INS official made a remark that shattered my reality.

“I understand your daughter was adopted, correct?”

My neck snapped to the right. My dad stared straight ahead.

“Yes,” he replied. He couldn’t look at me.

Whaaatttt?!?!

“From your brother, correct?”

“Yes,” he replied.

He fidgeted in his chair, ever so slightly. His eyes focused toward the front of the room.

I could sense my parents peeking at me from the corner of their eyes, checking to see if I was going to cry, yell, make a scene.

I knew better than to disrupt an INS hearing. I was well-trained.

My mind raced, but my expression stood stoic.

Adopted? What did that even mean? I didn’t know anyone who was adopted, other than my cat. We adopted him from the ASPCA. Maybe I came from a shelter, too?

And what does “from your brother” mean?

I sat silently for another hour, perhaps two. The brunette, oblivious to the bombshell she had dropped, continued paper-shuffling. After an eternity, she asked if I could sign my name in cursive.

“Yes,” I replied, forgetting about the adoption for a moment as a wave of indignation arose. Third-graders learned cursive. I was in fourth grade. Did I look like a measly little third-grader?

“Sign here,” she advised. I obeyed, executing my “P”’s with a flourish. See, I knew cursive. Shows her.

“Congratulations.” She smiled.

I had become a U.S. citizen. I could vote in another nine years. Great. Now could I get out of here?

****

I don’t remember leaving the INS building. It must have been an awkward walk.

My next memory takes place inside a Baskin-Robbins. My parents bought me ice cream and explained the messy circumstances of my birth.

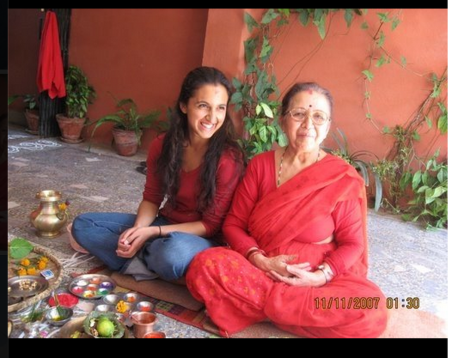

My parents had an arranged marriage at age 13. By the time they turned 43, they hadn’t conceived. It was the mid-1980’s; in-vitro fertilization wasn’t as advanced as it is today. They had wanted a child throughout their 30-year marriage. (They’ve now been married 58 years).

Meanwhile, my adoptive dads’ brothers’ wife was 7 months pregnant. The brother and his wife were excited about their child: they had been buying clothes, planning the nursery, discussing names.

But then an idea flashed into my adoptive dad’s mind. His brother and sister-in-law already had two daughters. Could he adopt baby number three? Could he and his wife have a shot?

He called his brother and pitched the idea. In the ultimate act of generosity, my birth parents agreed. They wanted to gift my adoptive parents with the opportunity that nature denied.

****

People see what they want to see. I prefer to believe that the world is a good place; that humans are innately kind, giving and empathetic.

What blows my mind, though, is the knowledge that I’m living proof.