“A blindfolded monkey throwing darts at a newspaper’s financial pages could beat most experts.”

Princeton professor Burton Malkiel uttered that slam against Wall Street stock traders back in 1973.

He claimed that despite their fancy-pants degrees, professional traders can’t predict the future any better than … well … a blindfolded monkey. His book around that topic became a mega-bestseller and investing classic.

I love wagering real-life money on ridiculous experiments. One year ago, I put his statement to the test.

Well, kinda.

I had trouble finding a monkey. And I can’t train my cats to throw darts. (Grrow!)

So I blindfolded myself, flung darts at a list of stocks, and bought the first 10 that I hit.

These included Viacom, Nike, Kellogg’s, Nokia, Discovery Communications, Berkshire Hathaway, Unilever and a few more. I put $100 into each.

Fast-forward one year: What happened? And what lessons — if any — can we learn?

Don’t Wager the House

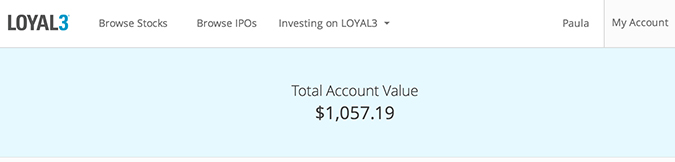

In the past 12 months, I’ve gained a grand total of …. (drumroll, please) … $57.19!

I’m rich, baby!

In all seriousness, that’s a pathetic little gain, and not just in raw dollars: $57.19 on an investment of $1,000 is a total gain of less than 6 percent.

“Hey, at least you gained instead of lost!”

While I appreciate the optimism, that’s not how you should view investments. Investing isn’t a game of playing-not-to-lose. That’s all defense; no offense.

Here’s a better mental framework:

- Opportunity Cost – What opportunities did I miss by keeping my money tied up? What’s the next best alternative?

- Risk – Does the reward reflect the risk?

- Diversification – Got it? Or not?

- Fees – Trading fees literally spell the difference between gain or loss.

Let’s check these out.

Opportunity and Risk

Pop quiz:

- You earn $100 in a savings account.

- You earn $100 investing in Enron stock.

Does $100 = $100? Are these two investments equivalent?

Nope.

Alright, second question:

- You earn 1.5% in a savings account.

- You earn 1.5% in GM stock.

Does 1.5% = 1.5%? Are these investments interchangeable?

Nope.

Contextualize your investments. In the context of risk, X does not equal X.

Wall Street pros will analyze an investment’s “risk-adjusted return,” which they calculate using a long string of Greek letters. They measure risk in five ways: alpha, beta, r-squared, standard deviation, and the Sharpe Ratio. (Unless you’re a Jeopardy contestant, you don’t need to remember that.)

“Why measure risk in five ways? Isn’t that redundant?”

Because this concept is so important that it’s worth crunching numbers from multiple angles. (It’s the same reason we use at least three formulas to crunch rental property numbers.)

You’re a normal human, not a financial professional (zing!), which means you don’t need to bother computing Greek formulas as long as you keep the concept of a risk-adjusted return in mind.

Don’t assume that X = X when one represents a Treasury bill and the other represents emerging markets.

You can’t say X = X when one represents a luxury rental in Silicon Valley and the other represents a dilapidated shack in a war zone.

“Cool, got it. But what does this have to do with your blindfolded-monkey experiment?”

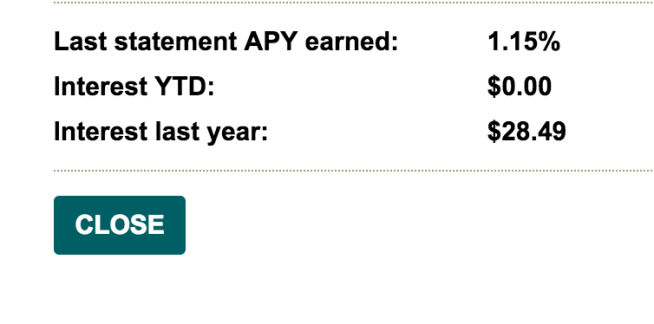

As a control, I also invested $2,000 into a high-yield savings account. Those savings landed me $28.49.

Result:

-

- I pocketed a virtually-risk-free $14 gain in the savings account

- I walked away with a high-risk $57 gain in stocks

— both with the same initial $1,000 investment.

“But you were certain to earn about $14 on your savings account. Heck, your principle is even FDIC-insured, the epitome of safety. By contrast, you had the POTENTIAL to earn more — or lose more — with stock investing.”

Yes. That’s correct.

And that perfectly illustrates the concept of opportunity and risk. Investments create a strange type of mathematics in which the difference between $57 and $14 does not equal $43.

The difference is far more nuanced and complex — and ultimately, the best approach is to adopt a healthy mix of both strategies.

“That’s the conclusion? All this info, and the conclusion is ‘invest in a healthy mix of both?'”

Yep. You can read nutrition blogs all day long, but you know how the story ends: “eat a healthy mix of protein, carbs and fats.” Investing is similar.

We can argue until we’re blue in the face about the “best” ratio of protein to carbs to fats (or, in the world of investing, the best ratio of savings vs. stocks vs. bonds), but the final story is still (mostly) the same.

Heap a healthy mix of the good stuff onto your plate; enjoy the results.

Speaking of mixes —

Diversification

Individual stocks (Nike, Viacom, Coca-Cola, Tesla, GM) are volatile. They could turn into either Apple or Enron.

Given that I invested in 10 individual stocks, I exposed myself to a boatload of risk and roller-coaster volatility. In the context of that level of volatility, 6 percent returns are nothing to brag about.

“But you picked 10 stocks, not just 1. Isn’t that like a mutual fund?”

Nope. Most mutual funds have hundreds, if not thousands, of stocks.

- Index funds like the S&P 500 track (you guessed it) around 500 stocks.

- The Wilshire 5000 tracks …. around 3,698 stocks. Not 5,000. Don’t ask me why.

I reduced some risk by throwing darts at big-name, established companies (known as “large-caps,”) such as Nike, Kellogg’s and Nokia.

Because these are established behemoths, they’re less likely to crash-and-crater than teeny little startups that recently debuted on the trading floor.

But let’s look at how my results compare to the broad market.

- The S&P 500, an index that measures 500 large companies traded on the NYSE and NASDAQ, gained 12.6 percent last year.

- I gained 6 percent.

- I underperformed the overall market by half. Ouch!

By investing in an index fund that tracks the overall market — like the S&P 500 — I would have lower risk and higher returns.

By investing in a handful of individual stocks, I carried higher risk and ended up with lower returns.

Does this mean you should avoid individual stocks completely? No. But it illustrates that you shouldn’t wander into individual-stock-terrain with the bulk of your portfolio.

Put a little “fun money” into individual stocks, but keep the majority of your assets (like your 401k funds) in index funds and ETFs that track the overall market.