Shortly after Martin and Sierra Black married, they bought a beautiful 2,200-square-foot Victorian home near Boston.

From the outside, the couple looked like they had it all.

But something was wrong.

They were drowning in bills. They forked over $2,200 each month on mortgage payments, and another $600 per month on gasoline for their long commutes. They felt trapped.

“Buying that house meant buying a piece of the American Dream,” Sierra says, “but we both figured out pretty quickly that it wasn’t our dream.”

They attempted penny-pinching. But these attempts didn’t move the needle.

“I felt like I was bailing out a leaky boat with a teaspoon,” Sierra says.

After two years, the couple decided to target Big Wins. They downsized into a 1,500-square-foot home located close to work. Their commuting expenses dropped to near-zero, and their mortgage payments fell to $1,600.

Their savings — just from this single decision — came to $1,200 per month, or $14,400 per year. The couple now enjoys greater freedom and less stress.

Their success story, and many more, are highlighted in J.D. Roth’s new guide, Be Your Own CFO: The Unconventional Guide to Mastering Your Money.

J.D. Roth is the founder of Get Rich Slowly, hailed by TIME Magazine as one of the “Best Blogs of 2011” and by Money Magazine as the “Most Inspiring” finance blog.

His new guide is part of a bigger offering called Get Rich Slowly: The Course, which features:

- One “Money Monday” email each week for a year

- The 120-page Be Your Own CFO guide

- 18 audio interviews with finance and lifestyle personalities including Pat Flynn, Ramit Sethi, Gretchen Rubin, Jean Chatzky and … me!!

{{By the way, these are NOT affiliate links. I have zero financial interest in promoting this guide and this course. But I believe in it, and I highly recommend it. I read the entire guide in one sitting. It’s a masterpiece that pulls together decades of reading, thinking and synthesizing lessons about personal finance into one comprehensive manifesto.}}

This week, J.D. sat down for an exclusive interview with Afford Anything. Take it away, J.D.!

#1: J.D., introduce yourself to Afford Anything readers. Who are you?

My name is J.D. Roth, and I’m an accidental personal-finance expert. That is, I have no formal training in money or finance. I’ve learned everything I know through reading and real life.

I first got interested in personal finance about ten years ago. I was deep in debt and decided to get out. I started to read everything I could about money and applying the ideas to my life. To document my progress (and to make myself accountable), I started a blog called Get Rich Slowly, where I shared my success and my failures. To my surprise, the blog was wildly successful. People liked my honesty, my story-telling, and my quest to find quality info about money. And ironically, the site allowed me to get rich quickly.

Today, a decade after starting to pull my financial life together, I’ve written a book about money (Your Money: The Missing Manual), contributed the “Your Money” column to Entrepreneur magazine for more than three years, and shared my philosophy on countless other websites. My latest project is year-long Get Rich Slowly course, which takes everything I’ve learned in the past decade and makes it available in one neat package.

#2: You’re a serial entrepreneur. How did the notion of being the “CFO of You, Inc.” come about?

It’s an idea that’s been in the back of my head for a long time.

You see, I used to struggle mightily with managing my personal finances, but I never had problems running a business. My businesses were always profitable, and often very profitable. But my personal bank accounts? Nearly always empty.

At some point it occurred to me that I ought to manage my own money the way I managed money for a business. That’s one of the things that helped me get out of debt and build wealth. I’ve hinted at this over the years, but never made it a centerpiece of my philosophy until recently.

A couple of years ago, I began to use the “CFO of You, Inc.” metaphor when talking with friends and family who were struggling with money. When I did, something clicked for folks. They got it, you know? We all understand that in order for a business to survive it has to make a profit. It makes perfect sense. Once people see that managing their own money is no different, it becomes much easier for them to do hard things like cut back on spending and work extra hours to earn more money.

#3: One of my favorite parts of your guide is your discussion of “pyrrhic victories.” (I’ll admit, I had to look up that word: “a victory with such a devastating cost that it is tantamount to defeat.”)

You describe making your own laundry detergent, building your own furniture and even blogging-for-income as pyrrhic victories. Why?

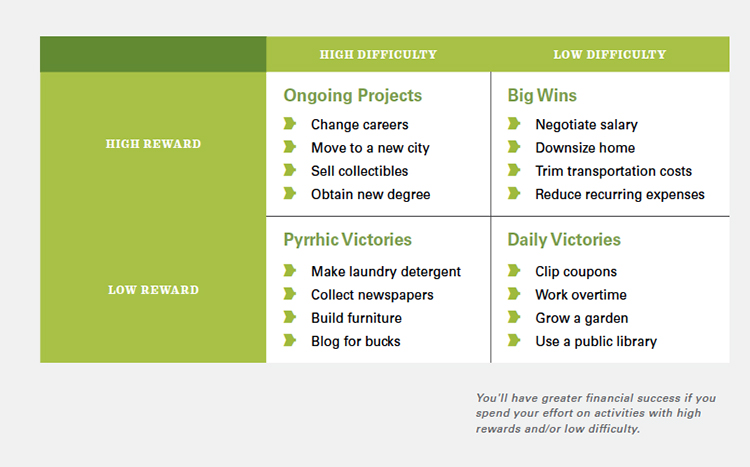

Not every path to profit is equal. Some actions provide little reward for the effort while others provide huge payoffs.

So, for instance, making your own laundry detergent is, indeed, a way to save money. Bravo to you if you do this. But you need to realize that it’s going to take you centuries to get out of debt or build wealth doing this. I’m not saying that you shouldn’t make your own laundry detergent or clip coupons or any of that stuff, but that you need to keep these activities in their place. You’ll have much better results focusing on what I call “big wins”.

Pyrrhic victories save you pennies (and often for hours of work). But big wins can save you thousands of dollars at a pop. Examples include downsizing your home, reducing your transportation costs, and negotiating your salary. My favorite example is this: The average American household spends something like $1400 a month on housing, which is nearly one-third of its budget. If the average family were to cut their housing costs in half, they’d save $700 per month, which is over $8000 per year. That is a big win. You could clip coupons for the rest of your life and never save $8000.

#4: How do you discern a pyrrhic victory from a legitimate/worthy victory?

A pyrrhic victory is one where you’re doing a lot of work for very little in return. Again, it’s not a bad thing to clip coupons or make your own laundry detergent. But I think it’s foolish to do this stuff while you’re paying for a huge house and driving a new car. Frugal habits are good to have, but they’ll never make you rich. At least not quickly.

I think it’s a good idea to sit down and brainstorm a list of all the ways you could boost your saving rate (or “profit”, as I call it in the “Be Your Own CFO” guide). Get all of these out of your head and onto paper. Nothing’s too crazy to consider. Once you’ve made your list, prioritize the actions. For each item on the list, note both how much effort is required and how big the payoff will be. “Bike to work”, for instance, might require a moderate amount of effort, but it yields huge payoffs. Not only do you save money on maintenance and fuel, but you also gain added health benefits that are worth a lot of money.

#5: In your guide, you focus on Big Wins: slashing the costs of housing, transportation and food. Why emphasize these three items?

These are the three areas where the average person can make the greatest impact on their bottom line.

Housing is, by far, the largest expense in most American budgets. As I said, about a third of our spending goes toward shelter. That’s insane! The average business, on the other hand, spends less than ten percent of its budget on facilities. If we were to manage our money the way businesses do, the average family would spend less than $500 per month on housing. That’s probably too extreme for most people, but I think it’s very reasonable to spend less than 20% of your budget on housing. Doing so provides huge financial rewards.

Transportation is the second-largest expense in the average American budget. Our society is pretty irrational when it comes to cars, actually. We lease. We buy new. We buy big. If you want to really make a difference to your financial life, let go of the need to drive a brand-new leased SUV. Choose instead to drive a used fuel-efficient vehicle, and drive it until it dies. Pocket the savings to use for something that really matters to you.

You can save even more by choosing to live in a walkable neighborhood. I’ve experienced this first-hand over the past few years. I used to live far from anything, so I had to drive (or bike) to get to places. Now, though, I can walk to just about everything I need. I only drive about once or twice a week. As a result, my transportation costs are much lower than they used to be.

Food is the last of the “big three” expenses in the average budget. It’s also the toughest place to trim costs. You can cut your housing or transportation costs in one fell swoop. (You could reduce your transportation costs to zero by the end of the day if you were to go sell your car and replace it with a bike.) But you can’t stop eating. You buy food over and over again. This is an area where you have to build frugal habits in order to repeatedly save a few bucks here and there. But if you do, the savings will accumulate over time.

#6: Why do so many blogs focus on Daily Victories rather than Big Wins?

Daily Victories are easy. They’re usually simple to accomplish, of course, but more than that they don’t challenge anybody’s sensibilities. When you suggest that readers ought to downsize their homes or ride the bus to work, people get pissed off. No, really. They immediately erect a wall of excuses for why these ideas won’t work for them, as if they’re some special snowflake. So, bloggers (and most other financial writers) stick to the safe stuff, the stuff that doesn’t offend anyone and the stuff that is easily done.

#7:In your guide, you mention that most frugal millionaires that you know spend between $24,000 – $36,000 per year. Can you elaborate on this?

You know, when I first read The Millionaire Next Door, I didn’t believe the authors when they said that most millionaires live in average neighborhoods, drive used cars, and wear normal clothes. But over the past few years, I’ve learned it’s true. Most of the millionaires I know are “quiet millionaires” who practice what Financial Samurai calls “steal wealth”.

A great example is my former neighbor, whom I’ve dubbed the real millionaire next door. John is a retired shop teacher. He lives in the same home he bought fifty years ago. He drove a Reliant K car until it dies a few years ago. He replaced it with a beat-up minivan from the 1990s. To him, a car isn’t a status symbol. It’s just a way to get around. He spends his money instead on the things that are important to him, such as his fishing boat in Alaska.

The other millionaires I know have similar stories. They spend very little in areas where most Americans spend a lot. They could afford fancier homes or cars or clothes, but they choose not spend on these things because they’re not concerned with what other people think. They have other priorities, and that’s where they focus their spending.

#8: Ideally, what percentage of a person’s income should they save? (Loaded question, I know.)

I think most people ought to save about half of their income.

I know, I know. A 50% saving rate seems extreme. I used to think so too. Most financial gurus recommend saving 10% of your income. If they’re bold, they’ll suggest 20%. These are the figures I used to recommend too. These numbers are a good place to start, but I think most people can and should do better. My ex-wife saves more than 30% of her income. She recognizes that saving isn’t a sacrifice. That money will still be spent. It’s just not being spent today on things that don’t matter to her. Instead, the money she saves will be spent sometime in the future on things she does care about. Saving isn’t sacrifice; it’s simply deferred spending.

And here’s another reason a high saving rate is important. In what Mr. Money Mustache calls the shockingly simple math behind early retirement, if you make some standard assumptions about inflation, withdrawal rates, and investment returns:

- A 10% saving rate means you’ll have to work about 45 years before you can retire. (Thus the reason many people retire at age 65.)

- With a 20% saving rate, you’ll have to work for about 35 years before taking “early” retirement at age 55.

- But with if you save 50% of your income, something amazing happens. You only need to save for about seventeen years. You can achieve Financial Independence before you turn forty!

- And if you have a personal profit margin of 70%? The folks who do this — and they exist, trust me — are able to quit working after only a decade.

The more you save, the sooner you can do the things you dream of doing.

#9: Many Afford Anything readers are entrepreneurs. How can they strike a balance between living frugally but also hiring, outsourcing and delegating when appropriate? How can they make that judgment call?

Well, there’s no one right answer. My motto has always been “do what works for you”, by which I mean you need to find the actions that are effective for helping you reach your goals and then do them. That said, I think there are two ways people can more easily make these judgment calls.

- First, be clear on your mission. In my “Be Your Own CFO” guide, I encourage folks to create a mission statement just like a company would. When you don’t have a clear direction, it’s easy to wander aimlessly. But when you have an end in mind, the path to success becomes clear. (Or clearer, at any rate.) Once you know your mission, you can set a series of goals that are aligned with this vision. And once you have those goals, you can better strike a balance.

- Next, it’s important to consider opportunity costs. Every time you make a choice, there’s a cost. By choosing to buy one item, you pass on the opportunity to purchase other items. By choosing to do one thing, you pass on the opportunity to spend your time in any other way. By spending mindfully — carefully thinking about each purchase — people can bring their budget in line with their purpose.

Here’s an example: My girlfriend thinks it’s crazy that I pay a housekeeper to clean our condo. “We could clean it ourselves!” she says. She’s right. We could. But you know what? By paying a housekeeper to clean eight hours per month, I free more than eight hours of my own time (because she’s more efficient at cleaning than I am). In the hours freed by hiring a housekeeper, I can (and do) write a handful of articles that earn me enough to pay her for an entire year. To me, that’s worth it. (Plus, I hate cleaning toilets.)

#10: Any parting words?

One of the best parts about writing the new Get Rich Slowly course was being able to share a complete, unified version of my financial philosophy, and to root it in this idea: Nobody cares more about your money than you do.

I believe strongly that in order to be financially successful, each of us must accept responsibility for our own life and situation. My fundamental premise is that you are the master of your own fate. You are the boss of you. Sure, you’re a part of the overall economy and subject to both lucky and unlucky breaks, but ultimately you are in charge. Your circumstances may not be your fault, but they’re your responsibility.

You don’t need anybody’s permission to get out of debt or to buy a house or to ask for a raise. And nobody’s going to come to you out of the blue to explain investing or health insurance or your credit card contract. Instead, you need to take charge of that stuff yourself. You must be independent, must develop an internal locus of control.

Here’s the bottom line: If you want to master your money, you must become the Chief Financial Officer of your own life. Your motto must be, “The buck stops here!” Don’t blame anyone or anything else for your financial situation, and don’t expect somebody else to rescue you. Your financial fate rests in your hands.

Check out Be Your Own CFO: The Unconventional Guide to Mastering Your Money.