Once upon a time, in southern California in 1994, there lived a man named William Bengen.⠀

His friends called him Bill.

Bill was born in Brooklyn, and he studied aeronautics at MIT. He wrote a big paper on advanced model rocketry. Then he became an executive at a soft drink company. Finally, 17 years later, he retired to sunny southern California.

Well, kinda.

Bill was smart and full of energy. He couldn’t stay retired for long. He decided to get a masters in financial planning. He opened his own firm.

And he started reading papers that … bemused him.

You see, at this time, many financial planners were claiming that since the stock market historically returns 7-9 percent compounding rates on average, retirees could withdraw and spend 7 percent of their portfolio. ⠀

⠀

Bill had a hunch that this was misguided. He decided to prove it.

He looked at 30-year timespans in U.S. history, starting from 1926. The first timespan ranged from 1926 to 1955. The second timespan ranged from 1927 to 1956. And so forth.⠀

⠀

He assumed that a retiree held 50 percent stocks, in the form of an S&P 500 Index, and 50 percent bonds, in the form of intermediate-term government bonds.⠀

⠀

Then he asked two questions:⠀

⠀

First, what was the worst-case scenario? Answer: retiring in 1966. The 16-year timespan from 1966 to 1982 was extra-rough. Enduring this at the start of retirement would make for one sad, sad puppy.

Second, how much could an investor sustainably withdraw from her portfolio during that worst-case scenario? The answer was 4.15 percent in the first year, and 4.15 percent, adjusted for inflation, every subsequent year.⠀

⠀

And thus, the 4 percent rule-of-thumb was born.

The 4 percent rule says a retiree can safely withdraw 4 percent of their portfolio in the first year of retirement, and 4 percent adjusted for inflation every year thereafter.

This has become a popular rule-of-thumb in the world of retirement planning. Here’s how it plays out:

- If you have a $1 million portfolio, you could withdraw $40,000 in Year One of retirement, and $40,000 adjusted for inflation every following year.

- If you have a $1.5 million portfolio, you could withdraw $60,000 in Year One.

- If you have a $2 million portfolio, you could withdraw $80,000 in Year One.

And so forth.

The corollary to the 4 percent rule is the “multiply by 25” rule. To figure out how much money you need to retire, multiply your yearly withdrawal rate by 25.

Let’s say you want to retire on $50,000 per year. Your rental properties collect $20,000 annually. If you want to generate the remaining $30,000 per year from your portfolio, you’d need an investment balance of $30,000 x 25 = $750,000.

Simple enough.

But it might be flawed.

Recently, I interviewed Dr. Wade Pfau on my podcast. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from Princeton and works as a professor of retirement planning.

And he has a few concerns about the 4 percent withdrawal rule.

Here’s the problem, Dr. Pfau says: the 4 percent withdrawal rule is based on 20th-century data. It assumes the markets will perform as well in the future as they did in the past.

But what if future markets don’t perform as well?

Other retirement thinkers have voiced similar concerns, leading some to advocate for a 3 percent withdrawal rule. (Eek!) But this is a depressing idea. Switching from 4 percent to 3 percent adds years to your cubicle-dwelling life. This changes the equation from “multiply by 25” to “multiply by 33.”

- If you want to withdraw $40,000 per year, the equation becomes $40,000 x 33 = $1.32 million.

- If you want to withdraw $60,000 per year, the equation becomes $60,000 x 33 = $1.98 million.

- If you want to withdraw $80,000 per year, the equation becomes $80,000 x 33 = $2.64 million.

Um, No. Thanks.

Any other ideas?

Fortunately, there are ways to salvage the 4 percent withdrawal rule. Here are a few palatable approaches.

#1: “Flexibility is the only true security.”

This quote from JL Collins — “as the winds change, so will my withdrawals” — says it all. When it comes to money management, all the spreadsheets and charts in the world can’t compare with good-ol’-fashioned flexibility.

Here’s how this applies:

The 4 percent withdrawal rule is built on the idea that you’ll increase your withdrawals at exactly the rate of the Consumer Price Index inflation.

But who does that??

Realistically, your spending habits won’t change at the rate of the CPI. Because you’re human. And that’s great, because it gives you options.

If you want to make the 4 percent withdrawal rule work, you could:

– Take out 4 percent without adjusting for inflation for a handful of years. For example, you could withdraw $60,000 per year (not adjusted for inflation) for the first 3-5 years, then make a one-time inflation adjustment, then hold steady for the next 3-5 years. This means you’re withdrawing slightly less money (in terms of purchasing power) every year, but you won’t “feel” the pinch as much. And doing this at the beginning of your retirement can make a massive compounding difference.

– Start a side hustle, such as freelancing or consulting, or participate in the “gig” economy, or launch a passion project. “Retirement” doesn’t have to be an old-fashioned, binary, from-this-moment-forward-I’m-not-going-to-earn-a-single-dollar straitjacket.

– Move to a country where the cost-of-living is cheaper. Try it for 6 months. Your worst-case scenario might be that you’ll spend the winter living on a tropical beach in Thailand or learning the local cooking techniques of Bali.

– Plain ol’ fashioned cutting back at home. Remember 2008? Remember how the “national mood” was one of frugality? I’m guessing that if there’s a serious market downturn, the attitude from your friends and family will be, “Hey, let’s watch Netflix tonight instead of hitting the bars.” You don’t need to live this way forever. Trimming back during recessions will make the biggest difference, since you won’t be converting paper losses into real losses.

#2: Create a “needs” bucket and a “wants” bucket.

One insight that Dr. Pfau shared is that we need a minimum baseline of money to survive. These are “needs.”

We also want extra money to fuel our lifestyle. These are “wants.”

“Duh, Sherlock,” you might be thinking. Bear with me.

Traditional retirement planning — including the 4 percent rule — lumps money for both needs and wants into the same bucket. But that might be a mistake.

Think about it. Why would you combine these two buckets together, when one is critical and one is discretionary?

Why would you expose the same level of risk to money that’s earmarked for groceries vs. trips to Italy?

The 4 percent rule assumes that all your retirement spending — both needs and wants — come from your portfolio. It assumes the same risk exposure, regardless of spending goal. And it doesn’t look at rental property income or other passive income, nor does it account for side hustle, gig economy, freelance or part-time income.

Flaws everywhere.

Try this instead:

Earmark some of your investments (or other income) to cover your basic needs. Keep these investments (relatively) conservative.

Then earmark another section of your investments (or other income) to cover your wants. Take more risks with this, if you choose.

Here are a few examples:

Needs – Your net cash flow from rental properties

Wants – Extra money from side hustles and passion projects

Needs – Laddered bonds (spaced evenly across months or years)

Wants – Stock index funds

Needs – The 3 percent rule of thumb

Wants – That extra 1 percent. (You’re still withdrawing at the 4 percent rate, but you can cut back if you need to).

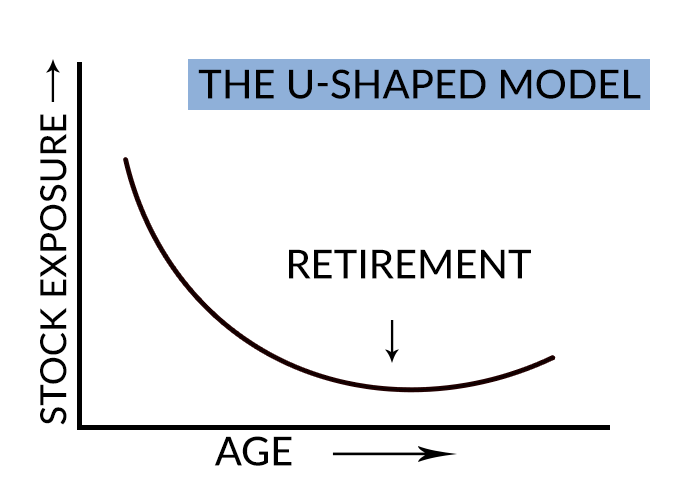

#3: Try a U-shaped stock model

This is a counterintuitive idea I’ve never heard before.

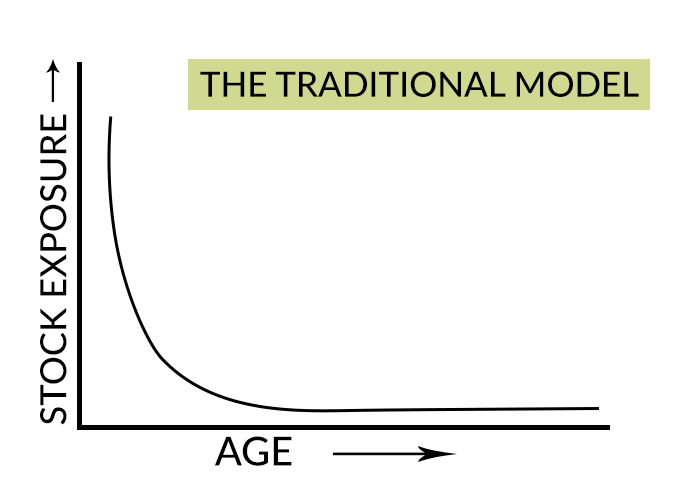

When you’re young, and retirement is far away, tilt your investments so that you’re more exposed to stocks and less exposed to bonds. (Okay, this is normal advice.)

As you approach retirement, rearrange your investments so that you’re less exposed to stocks, more to bonds. (Again, this is normal).

Here’s the wild card —

After you retire, start increasing your exposure to stocks again. (WTF?!)

The result is a U-shaped asset allocation model:

This is a huge departure from the traditional idea of constantly reducing your stock exposure over time, or keeping “your age in bonds” with the rest in stocks.

At first glance, this U-shaped concept seems counterintuitive. Your risk capacity — which is your ability to survive the rollercoaster of the market — declines as your timeline shortens. Less time; less capacity for risk.

So why would you accept MORE risk after you retire?

According to Dr. Pfau, this U-shaped model works mathematically because your timeline and risk capacity aren’t exactly hand-in-hand. “Risk capacity” is your ability to endure a market drop without compromising your lifestyle. Once you’ve made it past those critical first few years of retirement — assuming no major traumas at the onset — your portfolio could be strong enough to handle bigger swings.

Hmmm. This is a fascinating idea. I’m not sure if I agree with this or not, but I’ve never heard anything like it before, and the logic makes sense. I’m introducing it here as interesting food for thought.

TL;DR — The 4 percent rule-of-thumb might have flaws, but it’s still excellent for retirement planning, as long as you’re flexible. Flexibility is the only real security.

And when all else fails, move to Thailand.

Or get a job.

(Nahhhh.)